Newsletters 1996

Volume 18, Numbers 1 & 2, Spring/Summer 1996

Ray School-A Brief History

This history dated February 19, 1949, was written by Mrs. Leonora Root Wilson who described herself as "retired, but a teacher at Ray far45 years and seven months." She was the first teacher to start work in the original Ray School building known as the "South Park School". Our thanks to Rebecca ]anowitz for providing this article.

The first school in this vicinity was in the south end of the lot at the southwest comer of Monroe Ave. (now Kenwood) and 57th St. This lot was shaded by large oak trees; and the school house. which consisted of one room and a dressing room. was surrounded by beautiful lilac bushes. Pupils came from as far as 55th St. and Cottage Grove Ave. across what was then known as "Gansel's Prairie." This little school building was later made into an attractive two story house for one of the early settlers of Hyde Park.

My father, James P. Root. was president of the board of education of the Village of Hyde Park in the pioneer days. He was very anxious that a site should be secured in this neighborhood upon which a high school could be built at some future time. Many of the board of education members laughed at him and said that such a building would never be needed in "the bush", as this section of Hyde Park was nicknamed. However, in due time, the northeast comer of 57th St. and Kenwood Ave. was purchased as a school site. I believe there is a clause in the deed which reads that this property must always be used for school purposes. Here was built a two story frame building, used only for primary grades, and it was called "the South Park School." It was eventually moved to the section of the south side, then known as Parkside, and was used as a community church.

In June, 1886, the new Hyde Park High School was dedicated. At that time, Mr. WILLIAM H. RAY was principal of the high school which was at the northwest comer of 50th St. and Lake Park Ave., then known as Lake Ave. Mr. Ray and Carter H. Harrison, mayor of Chicago, addressed the

audience. 1he first floor of this building was used for elementary classes, as the high school then required only the upper floors, and Mr. Ray had the supervision of them, as well.

At this time an elementary school east of the Illinois Central was greatly desired by many of the parents whose children, in order to attend school. had to cross the tracks which were not elevated until 1893. Some of the property owners seriously objected to a school house in that residential section. Mr. lewis favored the plan and two of the members of the ''buildings and grounds committee" of the Hyde Park Board of Education who agreed with him were Dr. Henry Belfield, then president of the Chicago Manual Training School. and my oldest brother, Frederick K. Root.

In the summer of 1889, Hyde Park Village was annexed to the City of Chicago. Mr. Ray died in July of that year, and one of the teachers, William McAndrew, became principal of the high school. The elementary classes then acquired a separate supervisor, Miss Hattie A Burts, who had been principal of another Hyde Park elementary school, known as the Fifty-fourth Street School.

By 1892, the rapidly increasing high school enrollment made it necessary to find other quarters for the elementary pupils using the Kenwood Avenue building. These students were dispersed to three schools: Jackson Park School (on Fifty-sixth Street just east of the Illinois Central Tracks, the site of the present Bret Harte School), the Fifty-fourth Street School, and a temporary two-room building, known as the "Chicken Coop", which stood at the north end of the lot at 5631 Kimbark Avenue. At the same time construction of a new Hyde Park High School began on this lot. During the Columbian Exposition of 1893, students at the Chicken Coop were entertained alternately with Viennese waltzes from the Midway and hammering from the high school.

In September. 1894. the high school pupils were in the new building. and the former high school building on Kenwood, remodeled for elementary classes, was named the 'William H. Ray School".

Mr. William H. CW French was the first principal of the school, and also of the "Ray Branch", formerly the Jackson Park School. In his fifteen years as principal. Mr. CW French established the remarkable spirit of loyalty and friendship among his teachers which has persisted at Ray, and his death in July. 1910, was felt as a great loss in the community.

Mr. Arthur 0. Rape, principal from 1910-1930, supervised the transfer of the Ray School from its first location to the present address. Again the high school needed more room, and after the completion of the present Hyde Park High School at Sixty second Street and Stony Island Avenue, the old building on Kimbark was remodeled for an elementary school. On Friday, March 13, 1914, principal. teachers, pupils, and name moved to the present Ray School site.

Did you know?...

In July, 1916, Father Thomas Vincent Shannon was appointed pastor of St. Thomas the Apostle Parish. " ... his examination of the old parish school had convinced him that it wouldn't do. Fortunately, the old Ray Public School, three blocks away at Kenwood and

57th Street, was vacant. Father Shannon rented it and had a great semicircular sign placed over the doorway:

School of St. Thomas the Apostle.

When the school opened in September, 486 children were enrolled... the number of sisters was increased from six to twelve.

Uniforms were introduced-military for the boys (America was nearing her entry into World War I) and simple dresses for the girls. The children were proud of their uniforms... it gave a fine sense of democracy to the youngsters to find that they were all dressed alike, and that no one knew who was poor or who was rich." (from Centennial History of St. Thomas, 1969)

The old Ray Schoof was used by St. Thomas until 1929, when a new parish school building was completed.

THE NEW BUILDING

C.W. French, Principal

from the Hyde Park High School yearbook, 1893

Although the new high school building is not yet visible to the naked eye, it is by no means a "Castle in the Air." Toe necessity for it is obvious and pressing, and the delay in commencing work will, no doubt. be a short one.

It will be located on the east side of Kimbark avenue, between Fifty-sixth and Fifty-seventh streets, and will be complete in every particular. The details of the building cannot yet be definitely given, but its general features will be much as follows:

There will be two floors above the basement, with a large hall, forming a third story, which will be large enough for all the public exercises of the school. A gymnasium, with a hardwood floor, will occupy apart of the basement and first story. There will be three laboratories, especially fitted for biology, chemistry and physics, with all the necessary apparatus.

Another important feature will be a large art room. arranged for both mechanical and freehand drawing.

Instead of the old assembly room system, the pupils will be seated in class rooms, each room accommodating about fifty, while the whole building will have a seating capacity of 1,000, nearly double that of the present building. The ground plan will be so large that all the work can be done on two floors, thus doing away with the necessity of so much passing up and down stairs, an advantage that will be highly appreciated.

Toe old building is the center of many hallowed associations, and its walls are redolent with sweet memories of past joys and triumphs. Yet it is hoped that the new building may receive as its inheritance the successes of the old, and that it may maintain the honorable reputation which the past has established.

Cornell Awards 1996

To the Parish of St. Thomas the Apostle for the restoration of the church's terracotta tower which had been badly damaged by lightning some

year sago. The process required taking apart the uninjured tower, shipping the pieces to a firm in California where molds were made from those pieces, new terra cotta formed in those molds, and all shipped back to Chicago and assembled again.Dorothy Perrin, Chairman of the Art&EnvironmentCommittee atSt. Thomas accepted the award from BoardMember Devereux Bowly.

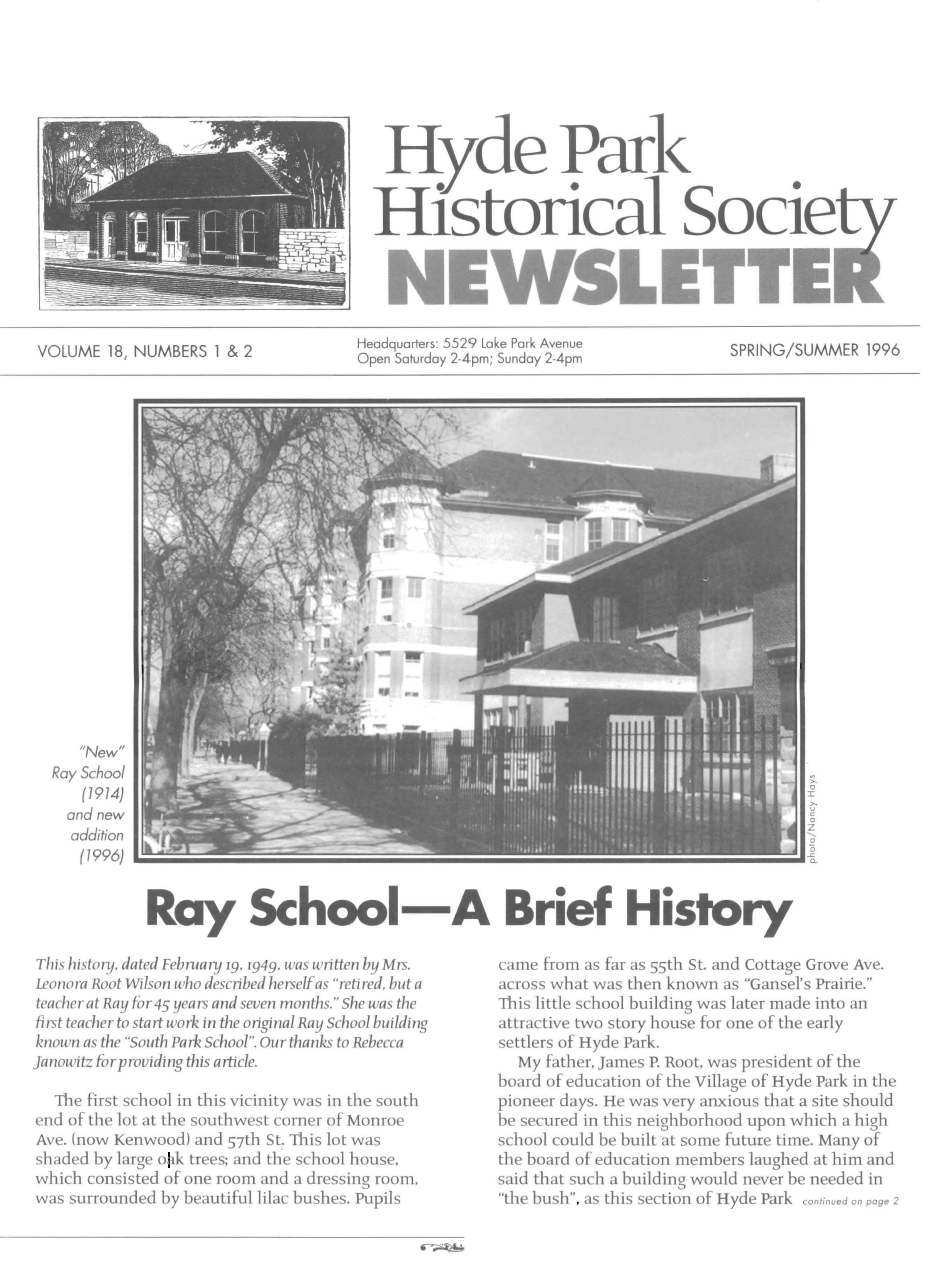

To the Public Building Commission of Chicago for the restoration of, and the addition to, the William H. Ray School both of which have been done with thoughtful and appropriate care-the replacement of the multi-paned windows, the roof and tuck pointing and the new addition. Chris Hill, Executive Director of the Public Buildings Commission, Adela Cepeda, Commissioner, and Cydney Fields, Principal of Ray School, accept the award.

To the Architectural Firm of Hasbrouck, Peterson, Zimoch and Siriratturnrong for providing the research for the restoration of the Washington Park Refectory. Architect Wilbert Hasbrouck in accepting the award told us that the cost of restoring this wonderful building was far less than tearing it down and building another.

Playground Memories

by Stephen A. Treffman

We have a tendency, sometimes, to assume that whatever was in place when and where we grew up had always been there or at least been there first. The remarkable new addition to the William Ray Elementary School stands on what was, for many years, the school's south playground. It is not an uncommon belief among Hyde Parkers that the playground must date to the same time that the school itself was built in 18g3. As this photographic postcard coop" and some ancillary structures, which stood almost directly across from 5630 S. Kimbark, had to be removed. Finally, stretching across the south end of tl1e block from the comer of Kimbark east to the alley were seven brick buildings, probably of mixed residential and commercial use.

Within a few years of this photograph, major changes were occurring in and around the school. The school population of Hyde Park and its surrounding neighborhoods had grown beyond the numbers that could be accommodated comfortably by a from 1910 clearly indicates, however, that was not the case; homes occupied the land that later would become the school's south and north playgrounds. In fact. at least by 18gJ, the half-block on which, three years later, the school would be built, was already well along in its residential and commercial development.

Homes and businesses could be found on three sides of that half-block area; the fourth side was an alley that split the block from north to south, a portion of which still exists. Six houses, most built in the 18&:Js, lined the north end of the half-block, where the primary class building now stands. Around the comer, on the east side of Kimbark Avenue, there were single family homes at 5611, 56r7, 5619, 5621 and 5647. At least some of these appear in the photograph. When the school was constructed, apparently only the "chicken configuration of public schools iliat reflected conditions of a much earlier period. Reflecting Hyde Park's dramatic population growth, its school enrollment rose from 76oo in 1gx, to 27,000 in 1912. Similar growth was occurring in Kenwood and Woodlawn, as it was throughout the city itself. Indeed, Chicago's population rose fifty percent from 1gx, to 1914. (Report of the Chicago Tmction and Subway Commission, Chicago: 1916) A new Hyde Park High School was built and opened in 1913 at 62nd and Stony Island Avenue. Students from the school on Kimbark transferred to ilie new high school. Students in ilie old Ray elementary school, pictured elsewhere in iliis issue, were shifted to the high school, which became the Ray School that we know today.

Progressive educational practices of the time called for young children to have opportunities to develop healthy bodies through outdoor play and recreation, hence, the need for elementary school playgrounds. Thus, as plans progressed to transform the old high school into an elementary school, establishing playgrounds for its students would have been one of the priorities. County records indicate that, by 1912, the Chicago Public Schools had begun condemnation proceedings against the East 57th Street buildings and probably all of the homes on the Ray School block. as well.

Changes in location of just one of those 57th Street businesses can be useful in suggesting to timetable for creation of, at least, the south playground. In the 18gos, Thomas A Hewitt opened a bookstore in one of those brick buildings on 57th. In 1 5. Hewitt, in partnership now with Vernon A Woodworth, moved the store a few doors west, to the larger and more prominent comer lot at 1302 E. 57th Street, apparently confident in the stability of that move. In early 1913, however, a building permit was issued to Woodworth, by then sole owner of the business, allowing construction across the street of the three story building that still stands at 1311 E. 57th. 1he building that housed the old store was demolished on April 24, 1914. It is likely that at about the same time, all of the houses along the Ray School block were razed or otherwise removed from their lots. It would appear, then, that the year in which that land, at least at the south end of the school. was converted into a playground was 1914, twenty-one years after the school itself was built.

Memories of the homes and stores that once were

there have long faded. Woodworth's book and school supplies store, however, remained in business in the building he had constructed, until it closed in 1972. Joseph O'Gara's bookstore then took over the space until recently, when he moved to new quarters two blocks east on 57th. Tracing the historical lineage of their business to Hewitt and Woodworth, O'Gara and his partner Douglas Wilson now lay claim to ownership of the oldest continuously operating bookstore in Chicago.

1he playground, where some of the defining events in the history of our community took place and, as well, in the lives of generations of many of its children, has now itself become a memory.

Envisioning those scenes again is made more difficult in the context of what is now so expansively new.

Sometime soon, young children will walk into the new school addition and have no awareness of the playground that so long existed there. A new cycle of memories will begin. Most everywhere one looks in Hyde Park, layers of its history abound that, once uncovered, challenge our perceptions of its past as well as of our own.

THE COLLAPSIBLE COLISEUM AND THE CROSS OF GOLD

Volume 18 Number 3 Autumn 1996

In the summer of 1895 "The Greatest Building on Earth" (so said the flag on its roof) was going up on 63d Street, a block west of Stony Island Avenue.

Inland Architect said "The Coliseum" was the biggest building erected in America since the Columbian Exposition, and its statistics were indeed awesome.

Longer than two football fields, it covered 51/2 acres of floor space and would seat 20,000 easily. Eleven enormous cantilever trusses spanned 218 feet of airspace, enclosing nearly a city block. A tower twenty stories high would dominate the neighborhood, its elevators rising to an observatory/cafe, with a roof-garden music-hall atop that, and at the pinnacle a giant electric searchlight visible for miles.

The Coliseum's mammoth steel skeleton was all but completed ...and then it happened.

At 11:10 p.m. on August 21 the immense framework collapsed. The appalling roar scared people off a standing train as far away as 47th Street.

Atdawnthenextmorning engineerswith long faces inspectedthe ruins todeterminethecause.Newspaperreporters licked their pencil points, eagertopinblameandexposeascandal.Buttherereallywasn'tany.Thecollapsewasevidently causedby some 75 tons oflumber having been stacked on the roofso as to bear too heavily upon the lasttruss put into place, one which was notyet completelybolted into the structureas a whole. There was no scandalinthedesign, declaredAmerican Architect andBuilding News (Boston): "Both architectandengineerbearnamesofthebestreputeinthe country." Justthe same, itdidnotnamethem

The engineer of the steelwork was in fact Carl Binder and the architect was S.S. Beman.

Solon S. Bemen, age 42, had designed the Pullman Building in his twenties, planned the whole village of Pullman, built the Studebaker-Fine Arts, the Washington Park Club at the racetrack, the Grand Central Station on Harrison at Wells, and the Mines and Mining Building at the world's fair. In Hyde Park/Kenwood, Beman designed Blackstone Library, the Bryson Apartments, Christ Scientist churches on Dorchester and Blackstone, eight or

ten private homes, and supervised the Rosalie Villas project (Harper between 57th and 59th). He himself lived on East 49th, moving later to

5502 Hyde Park Boulevard.

Of the collapsed Coliseum Beman spoke with authority. There was no doubt as to the correctness" of engineer Binder's steelwork, and construction would resume with no change in design as soon as new steel could be delivered. Barnum and

Bailey's Circus, booked there for October, would have to be cancelled, as would a fat stock and horse show.

But with 600 men working three shifts the Coliseum could be finished in 80 or 90 days, in time for a football game scheduled there for Thanksgiving Day. The Coliseum occupied the block just west of where Hyde Park High School stands today, between 62d and 63d Streets. Thus it stood exactly where Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show had ripped and roared during the world's fair in 1893. On the east and west it was bounded by Grace and Hope, interesting street names (they have been given confusing new ones lately), but the entrance to the Coliseum, as shown in our Harper's Weekly picture, was on 63d Street.

The Coliseum's tower gives the historian a problem. It has been so badly drawn in our Harperls picture as to be quite false---S.S. Beman could never have designed that thing. Was it added by a different hand when the sketch was mailed to the editors in New York?

Conceivably the $75,000 loss on the collapsed steelwork forced the Coliseum Company to curtail Beman's elaborate concept for the tower. But that there was finally a tower is suggested by the name given to the Tower Theatre, built on the identical spot after the death of the Coliseum. Old Hyde Parkers will remember a small steel latticework "tower" playfully capping the facade of the Tower Theatre as late as 1950.

Curiously, "The Greatest Building on Earth" is quite unknown today, and has apparently never had its story told before. A recent fat scholarly history of Chicago architecture from 1872 to 1922 knows nothing of it. Not even an authoritative 1985 study of Beman 's total work (which cites more than 100 of his buildings, including commercial projects) reveals any awareness of his mighty Coliseum. The reason must be its brief life. It rose, it fell, it rose again, it burned down-all in little more than two years. Sic transit gloria mundi. But before it died in flames, The Coliseum enjoyed one splendid moment of national fame.

That big moment came on July 7-11, 1896, when The Coliseum staged the Democratic National Convention, where William Jennings Bryan, age 36, made his famous Cross of Gold speech and was nominated for President of the United States.

The Chicago Tribune called the Coliseum arrangements "a grand success." Harper's Weekly compared The Coliseum to Madison Square Garden in New York, pronounced it typical of Chicago in its hugeness, and scoffed that no speaker could ever possibly be heard by all 20,000 sitting in that vast hall.

As for convention politicking, a headline declared it a horse race:

LEADERS ALL AT SEA.

No Certainty As To Probable Nominee.

Chicago papers printed dozens of portraits and cartoons of prominent Democrats. They ran reams of interviews with the leading candidates. But none of the portraits or cartoons or write-ups were about young William Jennings Bryan from Nebraska. That would change on the third day when the convention bosses let him speak.

The Cross of Gold was not a keynote speech, nor nominating or acceptance speech. Its purpose was to "conclude debate on the platform." It concluded it, all right. Bryan actually spoke about only one plank in the platform, the silver plank, but with it he ran away with the convention. It was like a classic myth, the one where the handsome young idealist from the provinces wins out over the old professional courtiers and is crowned prince.

The Democrats in 1896, at leastthe dominantfaction who engineered a plurality at the convention,werecallingforthefree,unlimitedcoinageofsilverbythe U.S. Mint at a ratio of 16to 1 with gold. "Wedemand,"saidtheplatform"thatthestandardsilverdollar be full legal tender, equally with gold, for alldebts,publicandprivate." Itdoesnotsoundradicaltoustoday,butin1896itwastomanygoodpeopleashockinginflationaryproposalto subvert a sacred gold standard. Some pro-gold, "sound-money" Democrats walked out and formed a splinter party.

In the severe depression of 1893-1894 there was a shortage of money in circulation. Bryan and other silverires in the agricultural West and South-for it was very much a sectional cause-believed that unlimited coining of silver would increase the money supply and thus ease the suffering of farmers and workingmen and small businessmen slipping toward bankruptcy.

It was a simplistic argument, no doubt-that Free Silver could cure complex economic ills, and social ones rising our of them. Bur by the summer of 1896 Free Silver had acquired a powerful appeal to the debtor class, and in his speech Bryan milked it to the maximum. He himself was sincere in feeling it nothing less than a holy cause.

I have lately read the Cross of Gold speech-it seemed the least I could do for this paper--expecting to be bored. Instead I found it fascinating: ardent in emotion, rich in striking metaphors, a masterpiece of old-fashioned populist oratory. No wonder its dramatic rhythms raised pulses in the Coliseum on July 9, 1896, when spoken out in Bryan's wonderful voice, with masterful timing and inflection, and clearly audible to all 20,000 in that enormous hall. (One marvels, since most Hyde Park ministers need a microphone to reach 50 listeners.)

That the Cross of Gold speech was nor to be a technical discourse on monetary policy was evident at once in Bryan's throbbing opener:

The humblest citizen in all the land,

when clad in the armor of a righteous cause, is stronger than all the hosts of error.

One cannot imagine Mr. Clinton or Mr. Dole trying to get away with that kind of language in 1996. But the transcript of the Cross of Gold speech which appeared in newspapers all over America the next day tells us of constant interruptions by applause from a thrilled audience. Bryan's listeners were soon rising to their feet to shout approval at nearly every other sentence of his attack on the bankers and gold standard capitalist money-centers of the East.

Bur it was Bryan's pro-silver finale that really set off

the fireworks. It has been a fixture in American folklore ever since:

We have petitioned [said Bryan]

and our petitions have been scorned; we have entreated,

and our entreaties

have been disregarded; we have begged,-

and they have mocked

when our calamity came.

We beg no longer;

we entreat no more;

we petition no more.

We defy them .. !

We will answer their demand for a gold standard

by saying to them:

You shall not press down upon the brow of labor

this crown of thorns,

you shall not [with outstretched arms] crucify mankind

upon a cross of gold.

Seconds later The Coliseum erupted in roaring delirium. Most accounts say the demonstration lasted nearly an hour. The Tribune reporter said fifteen minutes, bur then he objected to Bryan's "profane" last sentence, and besides, the Trib was a Republican paper and was supporting McKinley. The reporter for The Record, none other than young George Ade, another Republican, confided later that, "I didn't believe one word of thar'Cross of Gold' oratorical paroxysm, but it gave me the goose-pimples just the same." Byran, "The Boy Orator of the Platte," never much of an intellectual, had featured emotion over reason, and style over substance. Indeed, during the sustained tumult Governor Altgeld said to the man next to him, "I have been thinking over the speech. What did he say, anyhow?" And Clarence Darrow replied, "I don't know." Later, Senator Foraker, an old-guard Republican, made the wicked quip that in Nebraska the Platte River is "one inch deep and six miles wide at the mouth."

But in the Coliseum at the time, Bryan's speech was a sensational triumph, which swept the Democrats into an ecstasy of jubilation and made Bryan an instant national figure. Newspapers the next day showed him being carried on delegates' shoulders-"as if he had been a god," wrote Edgar Lee Masters. When Bryan could get away from the pressure cooker in The Coliseum, he and his young wife rode the El back to their Loop hotel, the modest Clifton House, where reporters again swarmed about him relentlessly. Bryan did not even attend the convention the next day when the delegates nominated him, at age 36, the youngest candidate for President in history.

The campaign of 1896 was a bitter one. To admiring throngs who turned out for Bryan's appearances, wrote Professor Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, Bryan seemed "a sort of knight-errant going about to redress the wrongs of a nation." But readers today would scarcely believe the apoplectic vituperation which gold standard advocates and

G.O.P. papers showered on Bryan and Free Silver.

In November he lost to McKinley 46% to 51% of the popular vote. He was nominated again in 1900, and (with Adlai E. Stevenson as veep) lost to McKinley again. A third time, in 1908, he lost to Taft.

Bryan and Free Silver and the unlucky Coliseum itself had seen their finest hour that day 100 summers ago down on 63d Street.

Notes from the Archives

by Stephen A. Treffman,

HPHS Archivist

The Hyde Park Historical Society has, over time, acquired for its archives a variety of older small artifacts and memorabilia from various businesses and other groups that once were or are still active in and around Hyde Park.

Among these have been such items as a miniature barrel bank from the University State Bank, a tape measure from the Acme Sheet Metal Works, a measuring glass from R.S.

from the Quadrangle Club, a 45 rpm record of piano music entitled "An Evening at Morton's," postcards, offering brochures for various real estate projects, and even stationary from the Woodlawn Businessmen's Association. If you would like to donate any older items imprinted with the names of businesses, clubs, groups or organizations in Hyde Park, we would be delighted to evaluate them for inclusion in our collection.

We also maintain a small collection of political memorabilia, primarily candidate pins, from various Hyde Park campaigns. Here again, if you have any items that you think might be appropriate for our archives, please write us a note or drop off donations enclosed in an envelope or other package at our headquarters at 5529 S. Lake Park Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637.

To the Editor:

I was very interested in your article on the Ray Schools in Spring/Summer issue. My mother and father were classmates at the original building-the St. Thomas the Apostle more recently. They would have been married, had they survived, for 96 years last June 8th.

In their class was one Matthew Brush-later to make millions on the short side of the stock market in 1931-35. My mother's maiden name being Hair their classmates took great joy and every opportunity to introduce Mr. Brush to Miss Hair.

I was born and brought up in Hyde Park. Our first home after I married was at S721 Kimbark where we lived on the third floor for several years and brought our first child home from the old Sc. Luke's Hospital in 1937.

We all miss Jean Friedberg Block.

Sincerely, Haward Lewis

Spanish Fort, Alabama

To the Editor:

The following note from Len Despres was written on the card above:

June 10, 1996

The accounts of the Ray School and William Ray are excellent. Some day someone might want to unravel the mystery of the "Skee Slide" at 47th and Drexel. Did it ever exist?

The photo below, from a book titled Chicago and its Makers, by Paul Gilbert and Charles Lee Bryson, published in 1929, seems to prove it did exist at 44th, not 47th, and Drexel. Too bad we've given up such local amenities!

Newsletters 1993

Volume 15 Number 1 and 2, February 1993

Annexation- Just in Time for the Fair

by Richard C. Bjorklund

Had it been up to long-ago voters in Hyde Park and Kenwood, Chicago now would be a smaller city bounded by 39th Street (Pershing Road), Fullerton Avenue, Pulaski Road and Lake Michigan, girded by strongly independent suburban municipalities.

In June, 1889, Chicago grew to four times its size, from 41 to more than 167 square miles, through votes favoring an nexation with the city in the City of Lake View, Jefferson Township, the Town of Lake, part of the Town of Cicero and the Village of Hyde Park. By this annexation, Chicago took its place as America's "Second City" with a population in excess of I million, more than any metropolis except New York.

Tne Great Annexation of 1889 was the second time Chicago had attempted to broaden its territory and tax base by annexing the Village of Hyde Park which in I 887 "won and lost (being part of Chicago) through a legal technicality," according to the Chicago Tribune.

That "legal technicality" barring annexation was found by Melville Weston Fuller, a lawyer for George "Duke" Pullman, who was vigorously opposed to his company town

- within the confines of Hyde Park - becoming part of the City of Chicago. By 1889, Pullman's lawyer was Mr. Chief Justice Fuller, appointed by President Grover Cleveland to serve 21 undistinguished years on the nation's highest court.

In the 1889 annexation vote, voters in the Village of Hyde Park turned out in significant numbers as 8,368 men, two thirds those eligible, cast 5,207 votes for annexation and 3,151 votes against, giving annexation a plurality of 2,046.

Communities within the Village of Hyde Park that strong ly favored annexation included Hegewisch, Grand Crossing, employees of the Illinois Steel Company as well as Colehour and Cummings which, the Tribune noted, were recently "visited by destructive fues" and were therefore inclined to want better fire protection.

Kenwood, "the aristocratic residence district par excel lance of the village", according to the Tribune, voted to stay out, 287 to 146. Hyde Park, the seat of the village government, rejected the proposition by a vote of 598 to 277. A harbinger of today's "lakefront politics" could be found in the vote of Edgewater and Uptown which also rejected annexation

There is a considerable irony in the rejection of annexation by Hyde Park and Kenwood because no area of Chicago immediately benefited more from the Great Annexation of 1889, called one of the four most significant dates in Chicago history by authors of "Chicago: Growth of a Metropolis."

Annexation was supported by civic and business interests in the city as well as by Chicago's newspapers because it was seen as a necessary prelude to the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893, the greatest civic achievement in the city's history, staged in Hyde Park on the Midway Plaisance.

Chicago wanted annexation to present to the world the image of a large and thriving urban area, one more expansive than the scant 41 square miles it had accumulated since incorporation in 1837. More than that, the city planned to float a $5 million general-obligation bond issue to support the creation of the Columbian Exposition; annexation would broaden the property-tax base.

Successive mayors Carter Harrison I, John Roche and Hempstead Washburne encouraged annexation, which was tried through the Cook County Board in 1887 and achieved through popular and City Council vote in 1889. Harrison was elected "World's Fair Mayor," only to suffer assassination at the hands of a disappointed job seeker only hours after he pronounced:

"Genius is but audacity, and the audacity of Chicago has chosen a star. It has looked upward to it, and knows nothing that it fears to attempt, and thus far has found nothing that it cannot accomplish."

Another annexation irony is found in the election of John Hopkins to succeed Harrison for the 1893-95 mayoral term. Hopkins, then an executive of Pullman Palace Car Co., op posed Hyde Park annexation in 1887 as an agent of his boss, George Pullman. But by 1889 as independent operator of Arcade Trading Co. in Pullman and Secord & Hopkins Co., a Kensington department store, he vigorously advocated an nexation. Hopkins, incidentally, was the first of many Irish Catholic mayors of Chicago.

George Pullman represented one strain of annexation foes whose chief objection to the proposal was that they would lose personal and political power in a merger with the city. There were, however, great numbers of sincere private citizens who had legitimate objections to the annexation proposal in Hyde Park and elsewhere. They feared bringing the vice and corruption of the central city to their suburban like communities where saloons, prostitution, shanties and, they believed, political corruption were unknown.

So deep ran the mistrust for Chicago and its political works that Charles S. Baker, treasurer of the Village of Hyde Park, insisted that the village board adopt a declaration that read:

"Whereas, the treasurer of Hyde Park and the Town of Lake hesitate and delay to pay over to the City of Chicago the money in their possession unless indemnifiei:I and other officers hesitate and delay to pay over the monies in their possession belonging to Chicago "

Chicago thereupon adopted an ordinance indemnifying Baker and others, leading to Annexation of the Village of Hyde Park, which became the 32nd Ward of Chicago from 39th to 55th Streets and the 33rd and 34th Wards south of 55th Street to the center line of State Street and east to Lake Michigan and State Line Road.

Citizens favoring annexation now looked forward to fulfillment of the promise of better municipal services, including water and sewerage, police protection and fire-department services. They also welcomed an end to petty rivalries among small, contentious units of government, including multiple school districts.

On July 15, 1889, Chicago added220,000citizens and 125 square miles of territory that became 34 of the city's present 50 wards and 53 of its 77 community areas. Forty-eight square miles of the new city land had been the Village of Hyde Park, which then contained the Chicago Jockey Club in Washington Park, South (now Jackson) Park that was soon to be the home of the World's Columbian Exposition, and Oak.woods Cemetery.

A meaningful footnote to the annexation of Hyde Park to the City of Chicago came on Saturday, July 15, 1939, when the Hyde Park Golden Jubilee Celebration was initiated in the Council Chambers of the City of Chicago to mark the 50th anniversary of annexation. Sponsor of the resolution for the jubilee was Ald. Paul H. Douglas (5th), who called attention to a community-wide celebration to be held from July 15 to

October 15 of 1939.

Letter from the Fair - 1893

John A. Campbell ( 1836-1909) of Butler, Indiana was a school teacher, insurance agent, diarist, writer, traveler, correspondent for the local weekly Courier. He kept a diary for over 50 years and wrote many newspaper columns about his journeys by train in the late 1800's. Ed Campbell is his grandson.

Ed Campbell is also treasurer of the Hyde Park Historical Society and a talented photographer whose exhibit "Struc tures in Hyde Park" is currently on display at Society Head quarters. The column below, written in /893 by Ed's grandfather, tells of his visit to the "Great Fair."

Your correspondent, intent on visiting the great Fair, failed to remember the COURIER last week and to make amends will indite this letter. We reached Chicago on the eve of the 16th of May and found no difficulty in obtaining good room and board at $1.50 per day. Wednesday we spent in visiting points of interest in the city and making business calls. Thursday we started early and reached the fair gates an hour too early. The delay seemed tedious, but it terminated, and we entered the enchanted place, and if not a building was open, one would be greatly benefited to see only the outside of the largest and most showy buildings to be seen in a group anywhere in the world. Our day was spent mainly in fixing bearings, studying the geography of the city and learning to distinguish one monster building from another, and after spending much time and indulging much thought, the enchantment of the place would frequently entangle us and we would be compelled to ask the aid of one of the two thousand gentlemanly guards for information. We started to visit the state buildings and commenced with Indiana, and, while she is bringing up the scattered, demoralized rear, yet, she has a very pretty building, neat without and within, still incomplete, but enough done to make a show of what it will be. One feature of the building is admirable--wide stairways of easy ascent and a long, wide portico that will shelter thousands of poor hot, tired Hoosiers in the near future. The fair would be a grand affair if one could change his weary legs and blistered feet for new ones about four times a day. This difficulty may be slightly modified at $7.50 per day by getting one of the 2,000 roller chairs and a stout wheelman to push it. Yet this is only an aggravation as somebody is always between you and what you want to see and moves only after you are tired waiting and have lost interest in something more

distant that you will perhaps get no further view of. So the only really satisfactory way is to tramp, tramp, until you are completely done for and then sit down and rest. The Nebras ka state building is an ornament to that great state, and its exhibit is worth a trip to Chicago. Washington comes in for a large share of praise for a unique building. One nowhere else of a similar form is found. It is built of huge pine and walnut logs about four feet in diameter and fifty feet long, surmounted by a frame structure of difficult description. Her exhibits are wonderful and perfect. The Dakotas have some what similar buildings and many rare exhibits. Idaho has a wonderfully old fashioned round log building large enough to entertain a half dozen corn husking bees. Pennsylvania comes in with an old fashioned frame house. Wide doors and windows with small lights of glass. Liberty bell is carefully enshrined within and thousands view it with wonder and awe. New York is outdoing herself and creating a palace of mag nificence nowhere else equaled. Her Public Hall is said to be unequaled anywhere for magnificence. No exhibit in the building to speak of. Florida has an odd shaped building in the form of a fort and is filled with the products of that sunny slope. The fish, turtle and sea products are so real that we smell fish for an hour after leaving her building. West Vir ginia, the Carolinas and some other states have small, un pretentious buildings, Kentucky being partially an exception. Well, my letter is outgrowing my intentions and I must draw it to a close and possibly resume the subject in the near future. The only trouble is, we can't tell it as it is, and the only way to realize the magnitude and grandeur of the Fair is to visit it.

May 20, 1893 J.A.C.

The Society plans to exhibit personal memorabilia of the Columbian Exposition beginning March 1. Loans of letters, articles, souvenirs and curiosities are invited from the com munity. All items will be acknowledged and returned at the close of the exhibit in November. Please bring items for the exhibit to the headquarters on Saturdays or Sundays between 2 and 4 pm.

Steve Treffma,n, our Society Archivist, shares a bit of history - unpleasant, but our history nonetheless - with us.

Notes from the Archives:

by Steve Treffman

Restrictive Covenants: The existence of race restrictive real estate covenants in Hyde Park during much of the second quarter of this century has received mention in several recent articles. In the December, 1991, issue of our Society's Newsletter, Leon M. Despres noted the importance these then legally enforceable agreements between property owners had in promoting racial segregation in Hyde Park. Margaret Fallers, in our June, 1992 issue, characterized these restrictive covenants as among the more shameful elements of Hyde Park history. Elsewhere, Stewart Winger, in the Spring/Sum mer 1992 issue of Chicago History, described in some detail the University of Chicago's role in support of the covenants.

To give some sense of the concrete reality of these covenants, excerpts are offered here from two documents of that era which are illustrative both of the actual language of these covenants and of some of the ways in which they were enforced. The first is dated February 24, 1932 and is a standard real estate property owner's agreement form presently in the archives of the United Church of Hyde Park. The agreement requires that any_transfer, lease or other arran gement regarding real estate covered by the covenant was to be subject to two binding qualifications:

1. The restriction that no part of said premises shall in any manner be used or occupied directly or indirectly by any negro (sic) or negroes, provided that this restriction shall not prevent the occupation, during the period of their employment, of janitors' or chauffeurs' quarters in the basement or in a barn or garage in the rear, or of servants' quarters by negro janitors, chauffeurs or house servants, respectively, actually employed as such for service in and about the premises by the rightful owner or occupant of said premises.

2. The restriction that no part of said premises shall be sold, given, conveyed or leased to any negro or negroes, and no permission or license to use or occupy any part thereof shall be given to any negro except house servants or janitors or chauffeurs employed thereon as aforesaid.

"Negro" was defined as:

every person having one-eighth part or more of negro blood or having any appreciable admixture of negro blood, and every person who is commonly known as a colored person.

Once signed by eighty percent of the owners of a block of contiguous properties, the form was then to be filed at the offices of the Cook County Recorder of Deeds or Registrar of Titles. It should be emphasized that this form was not unique to Hyde Park-Kenwood but was used throughout Chicago and, in similar formats, in other cities in the United States as well.

Community organizations were usually formed to promote and enforce the restrictive covenants. One such group, operating under the direction of a board made up of representatives of local real estate, banking and commercial interests, was the Hyde Park Property Owner's Association, Inc. with offices at 1548 E. 53rd Street. In November 1944, its executive director prepared a mimeographed two page "Special Report to Members," a copy of which now rests in our Society's archives. In this excerpt from that document, activities by the HPPO in support of the racial covenants were reported with pride:

1. In recent weeks this Association has investigated and eliminated the following incidents of Negro occupancy in Hyde Park.

(a) In a residence south of 55th Street and east of Wood lawn Avenue a Negro family occupied a basement apart ment for several weeks in violation of a property owncrs' agreement. The Association negotiated with the owner who caused the termination of the Negro tenancy. The property is now occupied by whites.

(b) In a rooming house south of 55th Street and east of University Avenue a room was rented to a white woman whose alleged husband was a Negro. These folks moved out subsequent to our investigation.

(c) A merchant on 55th Street rented the rear of his store for living purposes to a Negro woman. When this mer chant was advised that his action constituted a violation of the restrictive agreements, he caused the eviction of his tenant. This entire manner was adjusted within four days.

(d) the owner of a six apartment building near 53rd Street and west of Woodlawn Avenue contracted to sell her property through a Negro broker. She had been told that the purchaser was a Caucasian, but investigation by the Association disclosed that in fact the proposed purchaser was a Negro. The owner then authorized the Association to effect a cancellation of the sales contract (a) Another violation recently occurred in an apartment building on Hyde Park Boulevard. The situation was satisfactorily adjusted after a discussion with the owner there of."

Ironically, the successes the HPPO executive claimed may have been as much signs of weakness as of strength. Obvious ly, some landlords, whatever their motives, were presenting challenges to the restrictive covenants. Moreover, a significant portion of the community's white population had begun to express fundamental repugnance towards the covenant's racially discriminatory premise. Ultimately, of course, the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948 overturned legal enforcement of the covenants. With the onset of Hyde Park's post-war urban renewal, individuals rose to prominence who would become symbols of new community attitudes committed to racial fairness. These men and women became leaders in the renewal process, with Mr. Despres’ an obvious, though by no means singular, example, and, whether through political careers or roles in a variety of public and private institutions, they helped shape what would be a new era in Hyde Park history.

Studies of these periods in Hyde Park history will, no doubt, continue to be written. There are probably many readers of our newsletter who have memories of personal experiences or who have reports or other documents related to the eras of the religious and racially restrictive covenants or of urban renewal in the Hyde Park area. If you would like to share those memories or relevant documents, our Society would be eager to have them in our archives and available to future researchers.

For further reading: Julia Abramson, A Neighborhood Finds Itself (Chicago, 1959); Robert J. Blakely, "Earl B. Dickerson and Hyde Park," HPHS Newsletter, December 1986; St. Clair Drake and Howard R. Cayton, Black Metropolis (Chicago, 1945); Arnold R. Hirsch, Making the Second Ghetto: Race and Housing in Chicago, 1940-1960 (Cambridge, 1983); Herman H. Long and Charles Johnson, People vs. Property: Race Restrictive Covenants in Housing (Nashville, 1947); Thomas L. Philpott, The Slum and the Ghetto: Neighborhood Deterioration and Middle-Class Reform, Chicago 1880-1930 (New York, 1978); Clement E. Vose, Caucasians Only: The Supreme Court, the NAACP, and the Restrictive Covenant Cases (Berkeley, 1967); Robert

C. Weaver, The Negro Ghetto (New York, 1948); and Stewart Winger, "Unwelcome Neighbors," Chicago History Spring/Summer 1992, pp. 56-72.

Lia Treffman, Carol Bradford and Theresa McDermott provided research assistance in the preparation of this ar ticle.

World's Fair Footnote:

Some appreciation of the national magnitude of the World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 may be found in the adoption by both major political parties of planks in their 1892 party platforms endorsing and supporting the Chicago event.

Democrats meeting in Chicago said on June 22: "Recognizing the World's Columbian Exposition as a national undertaking of vast importance in which General Gorvenment has invited the co-operation of all the powers of the world, and approaching the acceptance by many of such powers of the invitation so extended, and the broad and liberal efforts being made by them to contribute to the grandeur of the undertaking, we are of the opinion that Congress should make such necessary financial provisions as shall be requisite to the maintenance of the national honor and public faith."

Republicans meeting later that month in Minneapolis concurred: "The World's Columbian Exposition is a great national undertaking, and Congress should promptly enact such reasonable legislation in aid thereof as will insure a discharge of the expenses and obligations incident thereto, and the attainment of results commensurate with the dignity and progress of the nation.

THE WORK COTTAGE

The Chicago Landmarks Commission has decided against designating the Henry C. Work Cottage as a landmark partly because of its inaccessibility and partly because of the objec tions of the owner. However, the Commission has provided an interesting history of the house and its builder. We quote below some of their findings. If you would like to read the entire report, you can find it at HPHS headquarters.

The cottage at the rear of 5317 Dorchester Avenue was built by Henry Work in either 1859 or '60 and occupied by him and his family during the years of his principal songwriting significance. In 1859, Work bought the property at 5317 Dorchester from the original subdividers, Paul Cornell and Hassan A. Hopkins, Cornell's uncle. His move to Hyde Park is corroborated by an 1859-60 directory as well as 1860 census data.

Residential settlement proceeded steadily during the '50s as Cornell began selling lots in the area bounded by 51st and 55th streets, Dorchester Avenue and the lake. As noted by Dominic Pacyga and Ellen Skerrett in Chicago, City of Neigh borhoods, "Hyde Park began to take on the characteristics of a small New England town, reflecting the background of most of its early residents." The character of the town was rein forced by its institutions, the First Presbyterian Church of Hyde Park being principal among them at the time. The congregation was organized in 1858, and built their first church at 53rd Street and Hyde Park Boulevard. Henry Work and his wife were among the organizers of the congregation. Work was also elected township clerk in 1864 and served two years.

TheWork Cottage is an example of the Carpenter's Gothic style. Characteristic features of the style visible on the Work House are the vertical board and batten siding and the steep roof pitch, both of which combine to give the design a strong vertical emphasis. The style also generally utilized pointed arch detailing, a shape seen in the window opening of the roof dormer on the north elevation. The abolitionist cause that Henry Work championed in song came naturally. Work was born in Middletown, Con necticut in 1832, the son of Alanson and Aurelia Work. His father was a militant abolitionist who, in 1835, moved his family to Quincy, Illinois, where the family's home became a station on the Underground Railroad. Though radical in his actions against slavery, Alanson Work's abolitionist feelings were not uncommon during the early-to-mid-nineteenth cen tury. The slavery issue was a persistent thorn in the side of American life from the time of the United States' inde pendence and as the nation matured, popular sentiment grew to eradicate the institution. Approximately 4,000 slaves es caped from Missouri through the Work homestead in Quincy. The elder Work was eventually tried and convicted by the State of Missouri for his a tivities. With the father's release from prison in 1845, the family returned to Middletown.

Henry Work received a standard education including study of Greek and Latin...through his studies Work also became familiar with musical notation. Musical composition proved a preoccupation as he wrote lyrics and melodies for his own satisfaction. By the time he was fourteen, however, Work's parents began to steer their son toward the more practical pursuit of learning a trade. Rejecting the tailoring profession suggested by his parents, Work found printing more suitable to his tastes, and in later years commented that whatever success he had achieved as a songwriter were attributable to the disciplines of the print trade.

At the same time Work was pursuing his printing career, he continued to teach himself music. The first recognition of Work's musical talents came in 1853 when Edwin P. Christ, of the Christy Minstrels, agreed to sing Work's We are Coming, Sister Mary at his concerts. Publication of the song gave Work more incentive to continue his song writing. Work was discouraged by his subsequent compositions and, by 1857 when he came to Chicago, he still regarded himself primarily as a printer.

The Civil War was a turning point in Work's songwriting efforts. The conflict and its nascent themes of patriotism and abolition apparently gave Work a focus for his songs which was not present before. In 1861, he wrote Brave Boys Are They, the first of a remarkable series of war songs. The song was bought by the Chicago music firm of Root & Cady and led to a contract for Work with that music publisher.

During the war years, Work produced a series of inspirational songs, including Kingdom Coming (1861), Grafted into the Army (1862), Babylon is Fallen (1863), Wake, Nicodemus (1864), and Marching Through Georgia (1865). Often the songs reflected the events and mood of the war, such as the somber tone of Song of Thousand Years (1863) revealing the prevailing pessimism of the Union following Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania. The songs were enormously popular.

Within seven months of its publication, Kingdom Coming had sold more than 20,000 copies, but, more significantly, reports were heard that within weeks of the song's printing, Kingdom Coming was being sung as an inspirational verse by slaves behind the Confederate lines.

The popularity of his partisan songs notwithstanding, Work's best remembered song of the period is probably the temperance ballad Come Home, Father (1864). Often recog nized by its opening line, "Father, dear father, come home with me now," the song is unrelenting in its pathos-so much so that Root & Cady offered free copies of the sheet music to anyone who could read it without weeping.

Work continued to write songs for Root & Cady through 1870, though he left Chicago, presumably in 1867 when he sold his house in Hyde Park. With the close of the Civil War, Work's composing career floundered. For the most part, his post-War songs were ordinary in subject sometimes fell into the vapid melodramatic tones common to many songs of the period. His apparent frustration with the public response o his songs is suggested by the fact that between 1867 and his death in 1884, Work wrote a little more than half the number of melodies he had composed from 1861 to 1866.

The simple ballad evidenced the best features of Work's songs, as noted by a contemporary critic:

His melodies are simple and natural but as unlike and varied as the emotions to which they give expression; but, whether grave or comic, they possess inspirational qualities that, as musical compositions, arouse the im agination and fasten themselves upon the memory of the hearer. In his songs, Mr. Work is distinguished by his use of plain Anglo-Saxon words. He discards frothy adjectives, all rant, all extravagance of lan guage, and like Dickens, relies upon the situation he creates. This is the source of his power over the human heart.

Though he continued to compose songs, none of them equalled the public regard of Grandfather's Clock or hi Ci il War melodies. Henry Work died in Hartford, Connecticut 111 1884, a tragic figure who had never been able to regain his audience.

REFLECTIONS

by Carol Bradford, Outgoing President, HPHS

Reflecting on my two-year term as president of this Society, I am impressed most of all by the dedicated efforts of so many of our board members.

Theresa McDermott continues to produce a wonderful newsletter with the help of our members who contribute lively and fascinating articles of historic interest.

Our exhibits included one by our own Ed Campbell, on the structures in Jackson Park. Anita Weinberg Miller presented her exhibit on Clarence Darrow, with an opening program by her mother, Lila Weinberg, Darrow's biographer. Other programs done by our own members were Margo Criscoula' s presentation of the life and early music of Hen y Clay Work, Leon Despres' recollections of his early years 111 Hyde Park, and a program by Zeus Preckwinkle in honor of the 125th anniversary of the Harvard School.

We took a tour of Riverside, Illinois in August '91, or ganized by Mary Lewis; and in August '92 to Pullman, planned by Zeus. . .

We have devoted more attention to our archives 111 these

years, under the supervision of Steve Treffman. Some of our more interesting acquisitions are a golden anniversary book of the South Shore Country Club, and the great photo collec tion of Charles Bloom. The board voted to earmark funds donated by the Jean Block family for the purchase of materials to be preserved in the archives. The past two years, we devoted our August board meeting to preservation of our own organization records. This job is not yet complete, but we have made a substantial beginning.

We are especially grateful to the members of LILAC (Landscaping Initiative for the LakePark Avenue Corridor) for their work to beautify the railroad embankment south of our building. The Society contributed to this project by in stalling outdoor faucets to assure that the plants could be watered as needed. I'm sure all of you appreciated the im provement in the appearance of our block last summer and fall.

Finally, our society was the recipient of a generous bequest of $2,000 from the estate of Carol Goldstein. Ms. Goldstein was a regular volunteer at our headquarters for several years before ill health made it necessary for her to retire.

As I leave office, I want to encourage our members to become personally involved in activities of the Society. Alta Blakely is always in need of volunteers at the headquarters. Other ways to help include the newsletter production, pro gram, exhibits, and membership committees. Please let our new president know how you would like to help.

It has been an honor to serve as president of the Society.

Thanks to each of you for your continued support.

Volume 15 Number 3 and 5 October 1993

The White City As It Was Current Exhibit at Society Headquarters

by Ed Campbell

If you have ever wondered how the Columbian Exposi tion of 1893 was laid out in Jackson Park, this exhibit of W.

H. Jackson's photographs of the Fair will give you a con cept of the grand ensemble as well as detailed views of the important buildings. Arranged in a sequence around Wooded Island, the 26 large format photographs establish relationships and furnish vistas of the impressive sweep of the classical facades in the setting of lagoons and formal canals and basins.

Beginning at the Administration Building (south west corner of the fair) the buildings of the Court of Honor are displayed: Machinery, Agriculture, the Watergate, Manufac turers and Liberal Arts, Electricity and Mines. North from here and west of Wooded Island are Transportation, the Choral Building, Horticulture, and the Woman's Building. At the r.orth end are the Palace of Fine Arts and State Build ings. South east are the Fisheries and the U.S. Gove,mment Buildings. Buildings of foreign countries are along the lakefront between 57th and 59th streets, except for Japan which has buildings on the north end of Wooded Island.

The circuit of the structures surrounding Wooded Island is completed at the colossal Manufacturers and Liberal Arts Building which extended 1687 feet north from the Court of Honor to the mid-point of the lagoon east of Wooded Is land. West of Stony Island, extending to Cottage Grove and between 59th and 60th Streets, was the Midway Plaisance which provided the setting for ethnic entertainment and the famous Ferris Wheel.

This overview establishes the space and location of the buildings. You are encouraged, however, to stop along your tour to read the notes regarding the structures which were provided by co-curator and archivist, Stephen Treffman. Be sides being extremely informative, the comments reflect keen insights from the contemporary point of view.

To supplement the exhibit of photographs, a collection of fascinating memorabilia is being shown: postcards of other buildings in Chicago a the time of the Fair, guidebooks to the Fair, and many other souvenirs. One curiosity is a "passport" with a photograph of the owner and dated coupons for each day the Fair was scheduled to be open.

We are grateful to Sam Hair for sending us another of his mother's delightful reminiscences ...

A Memoir Of Florence Cummings Hair

Compiled by Samuel Cummings Hair

The World's Columbian Exposition was planned for Chicago, to open on the 400th anniversary of Columbus' discovery of America, 1492. But it proved to be so tremen dous an undertaking, it could not be completed until the spring of '93. It was the most colossal fair ever seen, up to then, and I think it has never been equalled in beauty. It was actually a World's Fair with all countries represented.

Father & Mother went to the grand opening and, the follow ing week father took me to Chicago with him.

After a visit to the Board of Trade (the noisiest place I had ever been) we took the Ill. Central to Hyde Park and passed thro' one of the many entrances to the Fair. I was ten years old. I have never forgotten that first sight of the Fair. A high fence surrounded the exhibit grounds and complete ly hid from sight any part of the grandeur within and as soon as we had passed thro the tum-style father stopped me, put his arms on my shoulders from behind and said, "Let's just look for a moment."

I have no words to describe the miles of curving streets, the beautiful lagoons, or the magnificent classical buildings

-- all white, and elaborate. The "Court of Honor", with the gold statue of Liberty and the Peristyle were unforgettable.

The state buildings were many of them remarkable. Illinois had a particularly fine one and I was one of those deeply im pressed with a huge "picture" landscape made from com kernels: a mosaic I think of colored kernels.

I went to the fair ten times before it closed but, to me, it is remembered as one of the most uncomfortable summers ever endured. We had, in Clifton, over 60 house guests - mostly father's relatives, mother would tell you! Marston was a year old, we had no rain for 102 days, the cistern went dry (due partly to careless use of water by our guests) and we were forced to use the water from one artesian well which was "hard" and utterly improper for use for washing. The guests found that it was less expensive to sleep in Clifton and commute to the Fair on a cd'mmutation railroad tick et -- a very low rate being in force. So we were flooded

with Fowler relatives and mother put in an awful summer.Irene and I were, of course, turned out ofour bedroom andhadtosleepinthesmallstore-roomabovethekitchen(laterthe bathroom). This had one smallwest window. It was attheheadofthebackstairswherethekitchenheatwasfunnelled up most successfully and the room never cooled off.Thatrainlesssummerwasagreatworryforfather.Cropsburnedupandhehadmany"headaches

NOTES FROM THE ARCHIVES

by Stephen A. Trejfman Archivist to the Society

This summer the Hyde Park Historical Society has been celebrating the 100th anniversary of the World's Colum bian Exposition with an exhibition entitled "The White City As It Was." Curated by HPHS Board members Edward Campbell and Stephen Treffman, the exhibit features twen ty-six large format half-tone panoramic views of the fair selected from a set of eighty taken by the famed American landscape photographer William Henry Jackson (1843- 1942). Also on display at our headquarters are souvenirs of the fair and other related items.

Our Society is one of over fifty different institutions in the Chicago Metropolitan area which have joined in this centenary celebration through the presentation of a variety of programs and exhibits.1

Exhibits on Columbian Exposition themes, each varying in perspective, have been offered this year by such institu tions as the Chicago Historical Society, the Art Institute, the Harold Washington Library, the Terra Museum of

American Art, the Museum of Science and Industry, Glessner House, the Regenstein Library, the School of So cial Service Administration of The University of Chicago, the DuSable Museum of African American History and even Chicago's City Hall. Paralleling the experiences of these and other exhibits in the city, ours has been attracting large numbers of visitors. In response, the Board has decided to extend it through Sunday, November 28, 1993, one hundred years and a day after the fair, which had hosted over 27 million visitors, finally closed its doors.

The plan of our exhibit is to present the viewer with a sense of the overall layout of the exposition's fairgrounds. At the center of the exhibit is a map of Chicago published in 1890 that shows not only the city's new boundaries after annexation of Hyde Park Village but also the outline of the exposition's fairgrounds as they were first conceived and, with but one alteration, actually laid out. The Jackson prints are arranged in a manner suggestive of a walk through the fair from the Administration Building just east of the fair's main entrance at approximately 63rd Street and Stony Is land and, following a route north past the exposition's major buildings, arriving at the far edge of the fairgrounds at 56th Street between Stony Island and the lake. It ends by returning to the point where the "walk" began. To facilitate the process a map of the exposition and an exhibit guide have been prepared and are available to visitors at no cost.

The prints themselves hold significance beyond their subjects. Jackson and C.D. Arnold each have been charac terized as the exposition's official photographer. The confusion arises out of a set of circumstances that developed during the exposition itself. C.D. Arnold, in fact, was desig nated as "official photographer" by the Fair's Board of Directors and given the exclusive right to produce a range of photographic souvenirs of the fair. During that summer, however, a dispute arose between Arnold and the Board, ap parently over the copyrights to his photographs. This led the Fair's chief administrator, Daniel H. Burnham, to con tract with Jackson to produce a series of one hundred eleven-by-fourteen-inch negatives for a fee of $1000. The Board, however, chose not to use the prints and negatives that Jackson produced and turned them over to Arnold, who destroyed them. Fortuitously, Jackson had made a duplicate set of the negatives and, for another$1000, sold the rights to them to the White City Art Publishing Company. The publishing company then offered retouched half-toned reproductions of eighty of the prints to the public, either as complete books or by subscription wherein small portfolios of the prints were sent periodically by mail to subscribers' homes at atotal cost of$4.00. The series was entitled initially The WhiteCity (As it Was) (1894)and later as Jackson"sFamous Pictures of the World"sFair(1895).2

The White City Art Company was very aggressive in promoting the sale of Jackson's series and their efforts were well received. As a result, Jackson's views of the exposi tion had wide public exposure and prominence not only in the years after the fair but also well into this century. Col lections of half-tone prints by Arnold and other photog raphers were also published but those by Jackson "swept the market. "3 The nature of the views, the quality of the processes employed in producing the half-tone reproduc tions and the marketing of the results apparently made the difference. Arnold also produced memorable images of the Fair, but the larger body of his work and his reputation have tended to be eclipsed, perhaps unfairly, by other 19th Cen tury American photographers, including Jack on. For ex ample, a recent encyclopedia of photographers' biographies

contains a long entry on Jackson, referring to him as the "of ficial photographer of the Fair," but makes no reference at all to C.D. Arnold anywhere in the book.4 Two Arnold "real" photographs of scenes from the Fair that probably were available for sale to Fairgoers are presently on display at Regenstein library. Arnold's rare platinum print photographs of the Fair's construction were displayed at an exhibit which closed at the Art Institute earlier this summer.

Public exhibitions of this large a selection of the Jackson exposition prints are unusual and, in Chicago this anniver sary year, our Society's exhibit appears to be unique. Al though the half-tone prints are not rare, through the years many complete sets have been broken up and sold off in dividually by dealers. The actual photographic prints that Jackson produced and which were the basis for the prints in our exhibit, are, however, extremely rare. Archivists at the Chicago Historical Society, which has twelve photographs from the original Jackson series in its collection, have reported that the only complete set of which they are aware is in the Library of Congress. Moreover, the twelve CHS photographs now housed in their archives are, in a sense, dying, their sepia images graduaJly fading and losing detail.

The images in the half-tone reproductions of the Jackson prints, on the other hand, have generally remained sharp and fresh, although the paper on which they are printed has become rather fragile. Chicago's R.R. Donnelly and Sons' Lakeside Press, according to that company's archivist, printed the series by means of a process called

"planogravure" and used a heavy paper that held the ink par ticularly well. The photomechanical reprints of Jackson's work, then, have actually extended their useful lives and given them a popular recognition they might not otherwise have been accorded had they remained only as photographs.

Half-tone black and white reproduction methods and color lithographic processes dramatically affected the way in which the works of Jackson and other photographers and artists were made available to the public in the 1890s. Im-

proved half-tone black and white mechanical printing proce dures had made mass production of photographic images

far more accessible and affordable to consumers eager for these products. As a result, there was considerable competi tion among publishers to meet the demand for pictures of the fair.5 One recent bibliography of World's Columbian Exposition printed material contains entries for 167 view books or portfolios of views focussing on the fair that were produced during and after it closed.6

Visitors to our exhibit may see examples of works by other photographers which appeared in Shepp's World's Fair Photographed (Chicago, 1893) and in The Dream City (St. Louis, 1894) both of which were distributed to the public in the same manner as were Jackson's, that is, as separate subscription folios or bound volumes. The strides made in half-tone techniques were matched and even sur passed by those in color lithography. Examples of such progress are evident in some exposition views from Daniel

H. Bumham's The Book of the Builders (Chicago, 1894)

which are on permanent display at our headquarters but have particular relevance during this exhibit. Technology and demand, it would seem, were feeding upon one another. All of the prints in our exhibit, then, not only helped capture images of the Fair but were, in themselves, symbols of the technological progress that the Fair itself was celebrating.

To an extent unparalleled for any Fair in this country's history up to that time and perhaps since, a flood of Colum bian Exposition souvenirs was produced for public con sumption. Included were such things as banks, fans, jewelry, historical glass, silk ribbons, tape measures, paper weights, watches, wooden pieces, knives, locks, corkscrews, and toys and the list goes on. An estimated one thousand varieties of souvenir spoons were cast, as well as two thousand different commemorative tokens and medals.

As for books and printed paper items from the Fair, there are over 2400 entries included in the Dybwad and Bliss bib liography and a supplement is in preparation. All in all, there may be as many as eighty distinct categories of memorabilia from the Exposition, each with subcategories.

Wearefortunatetobeabletopresentamanageablenumber of these souvenirs for display at our headquarters: aminiaturerubyredpitcher,amilk glasscommemorativedish,ametalbox,aworker'sticketpass,ametalpaperweight, an embroideredhandkerchief and, of course, avariety of printed items, including an advertising map, a guide book, and some colorful postcards. Reproductions ofsixadmissionticketstotheFair as well as the first set of legally sanctioned picture postcards in the United States, issued in 1893 to honor the Exposition, are on display and are available for sale to the public a tour headquarters.

The World's Columbian Exposition had an enormous im pact on Hyde Park and some of its neighboring com munities as well. If nothing else, it hastened Hyde Park's transformation from a village to a part of Chicago's urban landscape. While the Museum of Science and Industry is often noted as the last building still standing from the Fair, the remnants of the now truncated Jackson Park elevated line, the Alley "L," built in anticipation of the Fair and which carried many thousands of visitors to the 63rd Street

entrance to the exposition, also remains. Most of its parts date back to 1893. That track helped accelerate the growth of Chicago's South Side. Another line of access to the fair, the Illinois Central Railroad tracks, were elevated and the now familiar overpasses were first constructed in order to allow the safe entry of visitors to the Fair.

Then, there is The University of Chicago, built on land donated by one of the promoters of the Fair, Marshall Field. In 1894, Field would fund a natural history collection in the old Palace of Fine Arts, thus establishing the Field Colum bian Museum, which in 1920 transferred its collection to its new home in Grant Park and became the Field Museum of Natural History. Civic boosters and builders were aware that the Exposition would be built near and simultaneously with the University's campus. The juxtaposition of the two would demonstrate yet another significant cultural mile stone in a city risen from the bitter ashes of 1871. The University, in turn, would anchor, support and accelerate the process of community growth and development which the exposition had helped to spark.

The Society expresses its gratitude to Beverly Allen for her generous and timely contribution of a complete set of the William Henry Jackson prints to our archives. We are gratefulas wellto Joe Clarkfrom Art Werks ofHyde Parkforhis gift ofthe 1890 map ofChicagoandto Leon andMarianDespres for their donationofthe book, TheDreamCity, to the Societyand to our exhibit.We wishto thankEleanor Campbell,MargaretModelung,MarshallPatner,andHarrietRylaarsdamfor the color andrichnesstheybroughtto our exhibitthroughtheir loan of ColumbianExpositionrelated itemsto the Society.A grant fromthe JeanBlockArchivalFundassistedintheunderwritingofthisexhibit

Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs, Chicago '93 (Chicago, 1993).

2 Peter B. Hales, William Henry Jackson and the Transformation of the American Landscape, (Philadelphia, 1988), pp.202-209.

3 Ibid., p. 209.

4 Macmillan Biographical Encyclopedia of Photographic Artists and Innovators, (New York, 1983).

5 A review of this competition is expected next year with the publication by the University of Arizona Press of Julie K. Brown's book, Contesting Images: Photography and the World's Columbian Exposition.

6 G. L. Dybwad and Joy V. Bliss, Annotated Bibliog raphy: World's Columbian Exposition. Chica o. 1893, (Albuquerque: The Book Stops here, Publishers, 1992).

Our sincere thanks to HPHS Board Member Jim Stronks who found these wonderful word-pictures and most of the drawings in the century-old magazines indicated.

Preliminary Glimpses of the Fair

from Century Magazine-February, 1893

"Great is Staff"

Many of the smaller structures would be notable for beauty and for size if they were not here made pygmies by continuous grandeur. Like the larger buildings they were veneered with "staff." Great is "staff'! Without staff this free-hand sketch of what the world might have in solid ar chitecture, if it were rich enough, would not have been pos sible. With staff at his command, Nero could have afforded to fiddle at a fire at least once a year. One of the wonders of staff as seen at Chicago is its color. Grayish-white is its natural tone, and the basis of its success at Jackson park; but it will take any tint that one chooses to apply, and main tain a Ii veliness akin to the soft bloom of the human skin.

Staff is an expedient borrowed from the Latin countries and much cultivated in South America. Any child skilled in the mechanism of a mud pie can make it, after being provided with the gelatine molds and a water mixture of ce ment and plaster. How the workman appeared to enjoy seiz ing handfuls of excelsior or fiber, dipping them in the mixture and then sloshing the fibrous mush over the surface of the mold. When the staff has hardened, the resultant cast is definite, light and attractive. A workman may walk to his job with a square yard of the side of a marble palace under each arm and a Corinthian capital in each hand. While it is a little green it may be easily sawed and chiseled, and nails are used as in pine. Moreover rough joints are no objection, since a little wet plaster serves to weld the pieces into a finished surface.

In the rough climate ofLake Michiganstaffis expectedto last about six years, which the average life of the ablestEnglishministry.Greatisstaff!

A Dream City

Excerpts from Harper's Monthly-May 1893

"Getting There'

... one may reach the fair by land or by water, starting from Van Buren Street Station by steam-launch or steam boat, or by steam-cars which are part of the grimy equip ment of the Illinois Central Railroad. If by boat, and the day is fair and mild, it is a journey of the blessed, and the liquid course seems made to waft one gently toward the celestial city.