Newsletters 1996

Volume 18, Numbers 1 & 2, Spring/Summer 1996

Ray School-A Brief History

This history dated February 19, 1949, was written by Mrs. Leonora Root Wilson who described herself as "retired, but a teacher at Ray far45 years and seven months." She was the first teacher to start work in the original Ray School building known as the "South Park School". Our thanks to Rebecca ]anowitz for providing this article.

The first school in this vicinity was in the south end of the lot at the southwest comer of Monroe Ave. (now Kenwood) and 57th St. This lot was shaded by large oak trees; and the school house. which consisted of one room and a dressing room. was surrounded by beautiful lilac bushes. Pupils came from as far as 55th St. and Cottage Grove Ave. across what was then known as "Gansel's Prairie." This little school building was later made into an attractive two story house for one of the early settlers of Hyde Park.

My father, James P. Root. was president of the board of education of the Village of Hyde Park in the pioneer days. He was very anxious that a site should be secured in this neighborhood upon which a high school could be built at some future time. Many of the board of education members laughed at him and said that such a building would never be needed in "the bush", as this section of Hyde Park was nicknamed. However, in due time, the northeast comer of 57th St. and Kenwood Ave. was purchased as a school site. I believe there is a clause in the deed which reads that this property must always be used for school purposes. Here was built a two story frame building, used only for primary grades, and it was called "the South Park School." It was eventually moved to the section of the south side, then known as Parkside, and was used as a community church.

In June, 1886, the new Hyde Park High School was dedicated. At that time, Mr. WILLIAM H. RAY was principal of the high school which was at the northwest comer of 50th St. and Lake Park Ave., then known as Lake Ave. Mr. Ray and Carter H. Harrison, mayor of Chicago, addressed the

audience. 1he first floor of this building was used for elementary classes, as the high school then required only the upper floors, and Mr. Ray had the supervision of them, as well.

At this time an elementary school east of the Illinois Central was greatly desired by many of the parents whose children, in order to attend school. had to cross the tracks which were not elevated until 1893. Some of the property owners seriously objected to a school house in that residential section. Mr. lewis favored the plan and two of the members of the ''buildings and grounds committee" of the Hyde Park Board of Education who agreed with him were Dr. Henry Belfield, then president of the Chicago Manual Training School. and my oldest brother, Frederick K. Root.

In the summer of 1889, Hyde Park Village was annexed to the City of Chicago. Mr. Ray died in July of that year, and one of the teachers, William McAndrew, became principal of the high school. The elementary classes then acquired a separate supervisor, Miss Hattie A Burts, who had been principal of another Hyde Park elementary school, known as the Fifty-fourth Street School.

By 1892, the rapidly increasing high school enrollment made it necessary to find other quarters for the elementary pupils using the Kenwood Avenue building. These students were dispersed to three schools: Jackson Park School (on Fifty-sixth Street just east of the Illinois Central Tracks, the site of the present Bret Harte School), the Fifty-fourth Street School, and a temporary two-room building, known as the "Chicken Coop", which stood at the north end of the lot at 5631 Kimbark Avenue. At the same time construction of a new Hyde Park High School began on this lot. During the Columbian Exposition of 1893, students at the Chicken Coop were entertained alternately with Viennese waltzes from the Midway and hammering from the high school.

In September. 1894. the high school pupils were in the new building. and the former high school building on Kenwood, remodeled for elementary classes, was named the 'William H. Ray School".

Mr. William H. CW French was the first principal of the school, and also of the "Ray Branch", formerly the Jackson Park School. In his fifteen years as principal. Mr. CW French established the remarkable spirit of loyalty and friendship among his teachers which has persisted at Ray, and his death in July. 1910, was felt as a great loss in the community.

Mr. Arthur 0. Rape, principal from 1910-1930, supervised the transfer of the Ray School from its first location to the present address. Again the high school needed more room, and after the completion of the present Hyde Park High School at Sixty second Street and Stony Island Avenue, the old building on Kimbark was remodeled for an elementary school. On Friday, March 13, 1914, principal. teachers, pupils, and name moved to the present Ray School site.

Did you know?...

In July, 1916, Father Thomas Vincent Shannon was appointed pastor of St. Thomas the Apostle Parish. " ... his examination of the old parish school had convinced him that it wouldn't do. Fortunately, the old Ray Public School, three blocks away at Kenwood and

57th Street, was vacant. Father Shannon rented it and had a great semicircular sign placed over the doorway:

School of St. Thomas the Apostle.

When the school opened in September, 486 children were enrolled... the number of sisters was increased from six to twelve.

Uniforms were introduced-military for the boys (America was nearing her entry into World War I) and simple dresses for the girls. The children were proud of their uniforms... it gave a fine sense of democracy to the youngsters to find that they were all dressed alike, and that no one knew who was poor or who was rich." (from Centennial History of St. Thomas, 1969)

The old Ray Schoof was used by St. Thomas until 1929, when a new parish school building was completed.

THE NEW BUILDING

C.W. French, Principal

from the Hyde Park High School yearbook, 1893

Although the new high school building is not yet visible to the naked eye, it is by no means a "Castle in the Air." Toe necessity for it is obvious and pressing, and the delay in commencing work will, no doubt. be a short one.

It will be located on the east side of Kimbark avenue, between Fifty-sixth and Fifty-seventh streets, and will be complete in every particular. The details of the building cannot yet be definitely given, but its general features will be much as follows:

There will be two floors above the basement, with a large hall, forming a third story, which will be large enough for all the public exercises of the school. A gymnasium, with a hardwood floor, will occupy apart of the basement and first story. There will be three laboratories, especially fitted for biology, chemistry and physics, with all the necessary apparatus.

Another important feature will be a large art room. arranged for both mechanical and freehand drawing.

Instead of the old assembly room system, the pupils will be seated in class rooms, each room accommodating about fifty, while the whole building will have a seating capacity of 1,000, nearly double that of the present building. The ground plan will be so large that all the work can be done on two floors, thus doing away with the necessity of so much passing up and down stairs, an advantage that will be highly appreciated.

Toe old building is the center of many hallowed associations, and its walls are redolent with sweet memories of past joys and triumphs. Yet it is hoped that the new building may receive as its inheritance the successes of the old, and that it may maintain the honorable reputation which the past has established.

Cornell Awards 1996

To the Parish of St. Thomas the Apostle for the restoration of the church's terracotta tower which had been badly damaged by lightning some

year sago. The process required taking apart the uninjured tower, shipping the pieces to a firm in California where molds were made from those pieces, new terra cotta formed in those molds, and all shipped back to Chicago and assembled again.Dorothy Perrin, Chairman of the Art&EnvironmentCommittee atSt. Thomas accepted the award from BoardMember Devereux Bowly.

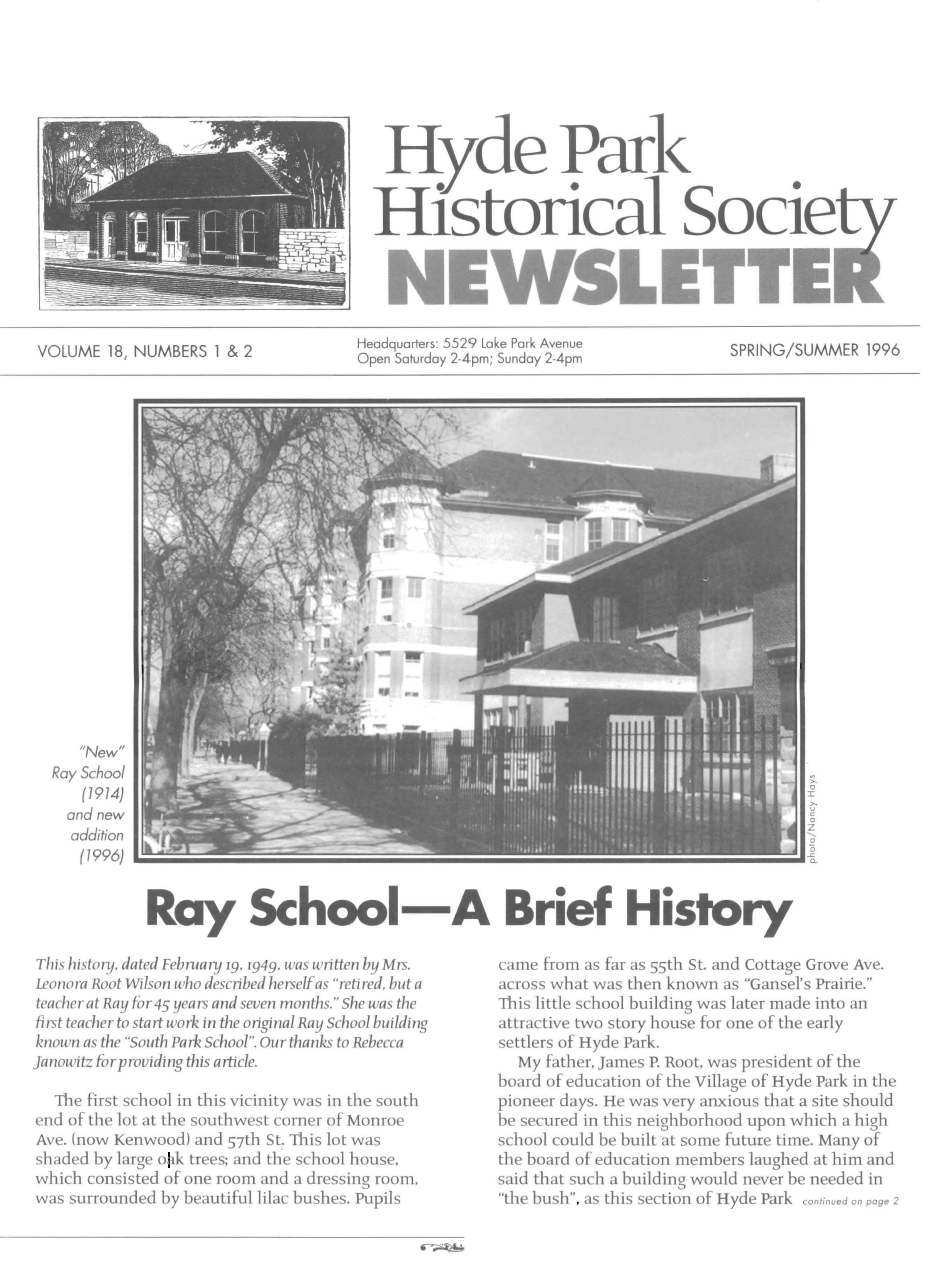

To the Public Building Commission of Chicago for the restoration of, and the addition to, the William H. Ray School both of which have been done with thoughtful and appropriate care-the replacement of the multi-paned windows, the roof and tuck pointing and the new addition. Chris Hill, Executive Director of the Public Buildings Commission, Adela Cepeda, Commissioner, and Cydney Fields, Principal of Ray School, accept the award.

To the Architectural Firm of Hasbrouck, Peterson, Zimoch and Siriratturnrong for providing the research for the restoration of the Washington Park Refectory. Architect Wilbert Hasbrouck in accepting the award told us that the cost of restoring this wonderful building was far less than tearing it down and building another.

Playground Memories

by Stephen A. Treffman

We have a tendency, sometimes, to assume that whatever was in place when and where we grew up had always been there or at least been there first. The remarkable new addition to the William Ray Elementary School stands on what was, for many years, the school's south playground. It is not an uncommon belief among Hyde Parkers that the playground must date to the same time that the school itself was built in 18g3. As this photographic postcard coop" and some ancillary structures, which stood almost directly across from 5630 S. Kimbark, had to be removed. Finally, stretching across the south end of tl1e block from the comer of Kimbark east to the alley were seven brick buildings, probably of mixed residential and commercial use.

Within a few years of this photograph, major changes were occurring in and around the school. The school population of Hyde Park and its surrounding neighborhoods had grown beyond the numbers that could be accommodated comfortably by a from 1910 clearly indicates, however, that was not the case; homes occupied the land that later would become the school's south and north playgrounds. In fact. at least by 18gJ, the half-block on which, three years later, the school would be built, was already well along in its residential and commercial development.

Homes and businesses could be found on three sides of that half-block area; the fourth side was an alley that split the block from north to south, a portion of which still exists. Six houses, most built in the 18&:Js, lined the north end of the half-block, where the primary class building now stands. Around the comer, on the east side of Kimbark Avenue, there were single family homes at 5611, 56r7, 5619, 5621 and 5647. At least some of these appear in the photograph. When the school was constructed, apparently only the "chicken configuration of public schools iliat reflected conditions of a much earlier period. Reflecting Hyde Park's dramatic population growth, its school enrollment rose from 76oo in 1gx, to 27,000 in 1912. Similar growth was occurring in Kenwood and Woodlawn, as it was throughout the city itself. Indeed, Chicago's population rose fifty percent from 1gx, to 1914. (Report of the Chicago Tmction and Subway Commission, Chicago: 1916) A new Hyde Park High School was built and opened in 1913 at 62nd and Stony Island Avenue. Students from the school on Kimbark transferred to ilie new high school. Students in ilie old Ray elementary school, pictured elsewhere in iliis issue, were shifted to the high school, which became the Ray School that we know today.

Progressive educational practices of the time called for young children to have opportunities to develop healthy bodies through outdoor play and recreation, hence, the need for elementary school playgrounds. Thus, as plans progressed to transform the old high school into an elementary school, establishing playgrounds for its students would have been one of the priorities. County records indicate that, by 1912, the Chicago Public Schools had begun condemnation proceedings against the East 57th Street buildings and probably all of the homes on the Ray School block. as well.

Changes in location of just one of those 57th Street businesses can be useful in suggesting to timetable for creation of, at least, the south playground. In the 18gos, Thomas A Hewitt opened a bookstore in one of those brick buildings on 57th. In 1 5. Hewitt, in partnership now with Vernon A Woodworth, moved the store a few doors west, to the larger and more prominent comer lot at 1302 E. 57th Street, apparently confident in the stability of that move. In early 1913, however, a building permit was issued to Woodworth, by then sole owner of the business, allowing construction across the street of the three story building that still stands at 1311 E. 57th. 1he building that housed the old store was demolished on April 24, 1914. It is likely that at about the same time, all of the houses along the Ray School block were razed or otherwise removed from their lots. It would appear, then, that the year in which that land, at least at the south end of the school. was converted into a playground was 1914, twenty-one years after the school itself was built.

Memories of the homes and stores that once were

there have long faded. Woodworth's book and school supplies store, however, remained in business in the building he had constructed, until it closed in 1972. Joseph O'Gara's bookstore then took over the space until recently, when he moved to new quarters two blocks east on 57th. Tracing the historical lineage of their business to Hewitt and Woodworth, O'Gara and his partner Douglas Wilson now lay claim to ownership of the oldest continuously operating bookstore in Chicago.

1he playground, where some of the defining events in the history of our community took place and, as well, in the lives of generations of many of its children, has now itself become a memory.

Envisioning those scenes again is made more difficult in the context of what is now so expansively new.

Sometime soon, young children will walk into the new school addition and have no awareness of the playground that so long existed there. A new cycle of memories will begin. Most everywhere one looks in Hyde Park, layers of its history abound that, once uncovered, challenge our perceptions of its past as well as of our own.

THE COLLAPSIBLE COLISEUM AND THE CROSS OF GOLD

Volume 18 Number 3 Autumn 1996

In the summer of 1895 "The Greatest Building on Earth" (so said the flag on its roof) was going up on 63d Street, a block west of Stony Island Avenue.

Inland Architect said "The Coliseum" was the biggest building erected in America since the Columbian Exposition, and its statistics were indeed awesome.

Longer than two football fields, it covered 51/2 acres of floor space and would seat 20,000 easily. Eleven enormous cantilever trusses spanned 218 feet of airspace, enclosing nearly a city block. A tower twenty stories high would dominate the neighborhood, its elevators rising to an observatory/cafe, with a roof-garden music-hall atop that, and at the pinnacle a giant electric searchlight visible for miles.

The Coliseum's mammoth steel skeleton was all but completed ...and then it happened.

At 11:10 p.m. on August 21 the immense framework collapsed. The appalling roar scared people off a standing train as far away as 47th Street.

Atdawnthenextmorning engineerswith long faces inspectedthe ruins todeterminethecause.Newspaperreporters licked their pencil points, eagertopinblameandexposeascandal.Buttherereallywasn'tany.Thecollapsewasevidently causedby some 75 tons oflumber having been stacked on the roofso as to bear too heavily upon the lasttruss put into place, one which was notyet completelybolted into the structureas a whole. There was no scandalinthedesign, declaredAmerican Architect andBuilding News (Boston): "Both architectandengineerbearnamesofthebestreputeinthe country." Justthe same, itdidnotnamethem

The engineer of the steelwork was in fact Carl Binder and the architect was S.S. Beman.

Solon S. Bemen, age 42, had designed the Pullman Building in his twenties, planned the whole village of Pullman, built the Studebaker-Fine Arts, the Washington Park Club at the racetrack, the Grand Central Station on Harrison at Wells, and the Mines and Mining Building at the world's fair. In Hyde Park/Kenwood, Beman designed Blackstone Library, the Bryson Apartments, Christ Scientist churches on Dorchester and Blackstone, eight or

ten private homes, and supervised the Rosalie Villas project (Harper between 57th and 59th). He himself lived on East 49th, moving later to

5502 Hyde Park Boulevard.

Of the collapsed Coliseum Beman spoke with authority. There was no doubt as to the correctness" of engineer Binder's steelwork, and construction would resume with no change in design as soon as new steel could be delivered. Barnum and

Bailey's Circus, booked there for October, would have to be cancelled, as would a fat stock and horse show.

But with 600 men working three shifts the Coliseum could be finished in 80 or 90 days, in time for a football game scheduled there for Thanksgiving Day. The Coliseum occupied the block just west of where Hyde Park High School stands today, between 62d and 63d Streets. Thus it stood exactly where Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show had ripped and roared during the world's fair in 1893. On the east and west it was bounded by Grace and Hope, interesting street names (they have been given confusing new ones lately), but the entrance to the Coliseum, as shown in our Harper's Weekly picture, was on 63d Street.

The Coliseum's tower gives the historian a problem. It has been so badly drawn in our Harperls picture as to be quite false---S.S. Beman could never have designed that thing. Was it added by a different hand when the sketch was mailed to the editors in New York?

Conceivably the $75,000 loss on the collapsed steelwork forced the Coliseum Company to curtail Beman's elaborate concept for the tower. But that there was finally a tower is suggested by the name given to the Tower Theatre, built on the identical spot after the death of the Coliseum. Old Hyde Parkers will remember a small steel latticework "tower" playfully capping the facade of the Tower Theatre as late as 1950.

Curiously, "The Greatest Building on Earth" is quite unknown today, and has apparently never had its story told before. A recent fat scholarly history of Chicago architecture from 1872 to 1922 knows nothing of it. Not even an authoritative 1985 study of Beman 's total work (which cites more than 100 of his buildings, including commercial projects) reveals any awareness of his mighty Coliseum. The reason must be its brief life. It rose, it fell, it rose again, it burned down-all in little more than two years. Sic transit gloria mundi. But before it died in flames, The Coliseum enjoyed one splendid moment of national fame.

That big moment came on July 7-11, 1896, when The Coliseum staged the Democratic National Convention, where William Jennings Bryan, age 36, made his famous Cross of Gold speech and was nominated for President of the United States.

The Chicago Tribune called the Coliseum arrangements "a grand success." Harper's Weekly compared The Coliseum to Madison Square Garden in New York, pronounced it typical of Chicago in its hugeness, and scoffed that no speaker could ever possibly be heard by all 20,000 sitting in that vast hall.

As for convention politicking, a headline declared it a horse race:

LEADERS ALL AT SEA.

No Certainty As To Probable Nominee.

Chicago papers printed dozens of portraits and cartoons of prominent Democrats. They ran reams of interviews with the leading candidates. But none of the portraits or cartoons or write-ups were about young William Jennings Bryan from Nebraska. That would change on the third day when the convention bosses let him speak.

The Cross of Gold was not a keynote speech, nor nominating or acceptance speech. Its purpose was to "conclude debate on the platform." It concluded it, all right. Bryan actually spoke about only one plank in the platform, the silver plank, but with it he ran away with the convention. It was like a classic myth, the one where the handsome young idealist from the provinces wins out over the old professional courtiers and is crowned prince.

The Democrats in 1896, at leastthe dominantfaction who engineered a plurality at the convention,werecallingforthefree,unlimitedcoinageofsilverbythe U.S. Mint at a ratio of 16to 1 with gold. "Wedemand,"saidtheplatform"thatthestandardsilverdollar be full legal tender, equally with gold, for alldebts,publicandprivate." Itdoesnotsoundradicaltoustoday,butin1896itwastomanygoodpeopleashockinginflationaryproposalto subvert a sacred gold standard. Some pro-gold, "sound-money" Democrats walked out and formed a splinter party.

In the severe depression of 1893-1894 there was a shortage of money in circulation. Bryan and other silverires in the agricultural West and South-for it was very much a sectional cause-believed that unlimited coining of silver would increase the money supply and thus ease the suffering of farmers and workingmen and small businessmen slipping toward bankruptcy.

It was a simplistic argument, no doubt-that Free Silver could cure complex economic ills, and social ones rising our of them. Bur by the summer of 1896 Free Silver had acquired a powerful appeal to the debtor class, and in his speech Bryan milked it to the maximum. He himself was sincere in feeling it nothing less than a holy cause.

I have lately read the Cross of Gold speech-it seemed the least I could do for this paper--expecting to be bored. Instead I found it fascinating: ardent in emotion, rich in striking metaphors, a masterpiece of old-fashioned populist oratory. No wonder its dramatic rhythms raised pulses in the Coliseum on July 9, 1896, when spoken out in Bryan's wonderful voice, with masterful timing and inflection, and clearly audible to all 20,000 in that enormous hall. (One marvels, since most Hyde Park ministers need a microphone to reach 50 listeners.)

That the Cross of Gold speech was nor to be a technical discourse on monetary policy was evident at once in Bryan's throbbing opener:

The humblest citizen in all the land,

when clad in the armor of a righteous cause, is stronger than all the hosts of error.

One cannot imagine Mr. Clinton or Mr. Dole trying to get away with that kind of language in 1996. But the transcript of the Cross of Gold speech which appeared in newspapers all over America the next day tells us of constant interruptions by applause from a thrilled audience. Bryan's listeners were soon rising to their feet to shout approval at nearly every other sentence of his attack on the bankers and gold standard capitalist money-centers of the East.

Bur it was Bryan's pro-silver finale that really set off

the fireworks. It has been a fixture in American folklore ever since:

We have petitioned [said Bryan]

and our petitions have been scorned; we have entreated,

and our entreaties

have been disregarded; we have begged,-

and they have mocked

when our calamity came.

We beg no longer;

we entreat no more;

we petition no more.

We defy them .. !

We will answer their demand for a gold standard

by saying to them:

You shall not press down upon the brow of labor

this crown of thorns,

you shall not [with outstretched arms] crucify mankind

upon a cross of gold.

Seconds later The Coliseum erupted in roaring delirium. Most accounts say the demonstration lasted nearly an hour. The Tribune reporter said fifteen minutes, bur then he objected to Bryan's "profane" last sentence, and besides, the Trib was a Republican paper and was supporting McKinley. The reporter for The Record, none other than young George Ade, another Republican, confided later that, "I didn't believe one word of thar'Cross of Gold' oratorical paroxysm, but it gave me the goose-pimples just the same." Byran, "The Boy Orator of the Platte," never much of an intellectual, had featured emotion over reason, and style over substance. Indeed, during the sustained tumult Governor Altgeld said to the man next to him, "I have been thinking over the speech. What did he say, anyhow?" And Clarence Darrow replied, "I don't know." Later, Senator Foraker, an old-guard Republican, made the wicked quip that in Nebraska the Platte River is "one inch deep and six miles wide at the mouth."

But in the Coliseum at the time, Bryan's speech was a sensational triumph, which swept the Democrats into an ecstasy of jubilation and made Bryan an instant national figure. Newspapers the next day showed him being carried on delegates' shoulders-"as if he had been a god," wrote Edgar Lee Masters. When Bryan could get away from the pressure cooker in The Coliseum, he and his young wife rode the El back to their Loop hotel, the modest Clifton House, where reporters again swarmed about him relentlessly. Bryan did not even attend the convention the next day when the delegates nominated him, at age 36, the youngest candidate for President in history.

The campaign of 1896 was a bitter one. To admiring throngs who turned out for Bryan's appearances, wrote Professor Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, Bryan seemed "a sort of knight-errant going about to redress the wrongs of a nation." But readers today would scarcely believe the apoplectic vituperation which gold standard advocates and

G.O.P. papers showered on Bryan and Free Silver.

In November he lost to McKinley 46% to 51% of the popular vote. He was nominated again in 1900, and (with Adlai E. Stevenson as veep) lost to McKinley again. A third time, in 1908, he lost to Taft.

Bryan and Free Silver and the unlucky Coliseum itself had seen their finest hour that day 100 summers ago down on 63d Street.

Notes from the Archives

by Stephen A. Treffman,

HPHS Archivist

The Hyde Park Historical Society has, over time, acquired for its archives a variety of older small artifacts and memorabilia from various businesses and other groups that once were or are still active in and around Hyde Park.

Among these have been such items as a miniature barrel bank from the University State Bank, a tape measure from the Acme Sheet Metal Works, a measuring glass from R.S.

from the Quadrangle Club, a 45 rpm record of piano music entitled "An Evening at Morton's," postcards, offering brochures for various real estate projects, and even stationary from the Woodlawn Businessmen's Association. If you would like to donate any older items imprinted with the names of businesses, clubs, groups or organizations in Hyde Park, we would be delighted to evaluate them for inclusion in our collection.

We also maintain a small collection of political memorabilia, primarily candidate pins, from various Hyde Park campaigns. Here again, if you have any items that you think might be appropriate for our archives, please write us a note or drop off donations enclosed in an envelope or other package at our headquarters at 5529 S. Lake Park Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637.

To the Editor:

I was very interested in your article on the Ray Schools in Spring/Summer issue. My mother and father were classmates at the original building-the St. Thomas the Apostle more recently. They would have been married, had they survived, for 96 years last June 8th.

In their class was one Matthew Brush-later to make millions on the short side of the stock market in 1931-35. My mother's maiden name being Hair their classmates took great joy and every opportunity to introduce Mr. Brush to Miss Hair.

I was born and brought up in Hyde Park. Our first home after I married was at S721 Kimbark where we lived on the third floor for several years and brought our first child home from the old Sc. Luke's Hospital in 1937.

We all miss Jean Friedberg Block.

Sincerely, Haward Lewis

Spanish Fort, Alabama

To the Editor:

The following note from Len Despres was written on the card above:

June 10, 1996

The accounts of the Ray School and William Ray are excellent. Some day someone might want to unravel the mystery of the "Skee Slide" at 47th and Drexel. Did it ever exist?

The photo below, from a book titled Chicago and its Makers, by Paul Gilbert and Charles Lee Bryson, published in 1929, seems to prove it did exist at 44th, not 47th, and Drexel. Too bad we've given up such local amenities!