Newsletters 2001

Volume 23, Number 1

When Tarzan Went to Harvard

By Edgar Rice Burroughs

Because I attended Harvard School sometime between the Pliocene and Pleistocene eras, Miss Schobinger has suggested that I write a little article for the School Annual and call it Before the Birth of Tarzan.... It was in 1888 that I entered the old Harvard School at 21st Street and Indiana Avenue, where my brother, Coleman, had been a student for a year. I was never a student-I just went to school there.

I lived over on the West Side where everybody made his money in those days and then moved to the South Side to show off. I kept my pony in a livery stable on Madison Street west of Robey Street... and in good weather I rode to school. In inclement weather, I took the Madison Street horse-cars to Wabash, a cable-car to 18th Street, and another horse-car to school. Sometimes, returning from school, I used to run down Madison Street from State Street to Lincoln Street, a matter of some three miles, to see how many horse-cars I could beat in that direction. It tires me all out even to think of it now. I must have been long on energy, if a trifle short on brains.

I cannot recall much about my classmates. Mancel Clark, Bennie Marshall, and I came over to Harvard together from Miss Coolie's Maplehurst School for Girls on the West Side-and were we glad to escape that blot on our escutcheons! There had been a diphtheria epidemic in the public schools the previous year, and our fond parents had prevailed upon Miss Coolie to take us in...

Bennie Marshall and I used to sneak down to the breakwater and smoke cubeb cigarettes and feel real devilish. I imagine we even chewed gum too. He> became a very famous Chicago architect (with Charles Eli Fox, he designed the Drake Hotel-Ed.) I can see him now sitting at his desk drawing pictures and chewing his tongue when he should have been studying.

At Harvard School I studied Greek and Latin because someone believed that they should be taught before English grammar was taken up; then I went to Andover and studied Greek and Latin all over again. So, having never studied English, I conceived the brilliant idea of taking up writing as my profession. Perhaps, had I studied English grammar, I would have known better, but then there would have been no Tarzan... There should be a moral to this. Perhaps it is that one should not smoke cubeb cigarettes.

REMEMBERING GWENDOLYN BROOKS

by Stephen A. Treffman, HPHS Archivist

"MAY THE NEW CENTURY SING TO YOU."

At our last annual meeting, HPHS had to be satisfied with giving Gwendolyn Brooks an award in absentia. In lieu of placing the Paul Cornell Award into her hands, we sent it to her accompanied by a copy of Bert Benade's remarks (see page 3) along with a report on how receptive our board and membership had been to the idea of granting her our 'award.

In an enthusiastic response, Ms. Brooks sent the Society two books, warmly inscribed, along with a

note gently reminding us that she was a working writer, one who wrote to be read, not celebrated. All the punctuation is hers. March 9, 2000 Hi! I thank you for your beautiful

Tribute! "Read" these books (I—as ifyou have TIME

Galore!)... before delivering to the Library! Gratefully

Gwen Brooks (I thank you ALL for honoring me!)

She gave us the second volume of her

"autobiography," Report from Part Tu'0. (Chicago, Third World Press, 1996) The inscription reads: For the

Library of the Hyde Park Historical Society. (May the NetC' Century SING to you!) Three large pink post-it-notes were inserted indicating stories she especially wanted us to notice: "My Mother, In Ghana," and "Black Woman in Russia.

The other book is a self-published work, Children Coming Home (Chicago, 1991). It consists of short poems expressing the reflections of children under stress as they arrive home from school.

Two additional books came to us last June. The inscription in Thirtx-First Annual Illinois Poet Laureate Awards 2000 (Chicago: privately printed) reads:

Thank you so much! For the copy of "Hyde Park History. " Yes, I'd appreciate two or three extra copies. I hope you enjoy the young people's poems. I gave 45 prizes of $ 100 each on June 12 at the U. of C. I'm so proud of them!"

Each page contains a single winning poem. At the bottom of each sheet is written, in Gwendolyn Brooks' hand, the name of the student, his or her age, grade and school. She had good reason to be proud of them. In the introduction, she addressed this note to the winners:

Congratulations!... on winning your Illinois Poet Laureate Award! I am proud ofyou, and I am proud to meet you. I appreciate yonr respect for poetry and interest in experimenting with language-with sound and texture and

manner.

All of your life, poetry can be a nourishing gift to yourself a Performance to enjoy and change; an irresistible influence.

Gwendolyn Brooks, an extraordinarily perceptive witness of our corner of the world, "sang" to us for more than half of the last century. She crafted deceptively simple lines of verse that communicated profound insights, enlightened us and enriched the world in which we live. We are grateful to have had her among us, honored that we could call her one of our own and were drawn more closely into community because of what she did with her life. We feel especially fortunate that we had the opportunity to tell her so while she was still among us.

PRESENTATION OF

THE PAUL CORNELL

AWARD TO

GWENDOLYN BROOKS

HPHS ANNUAL MEETING, FEBRUARY 26, 2000

Remarks by Berrt Benade

Our final awardee is the Poet Laureate of Illinois, Gwendolyn Brooks. We are sorry that she cannot be with us tonight. But, in a way, I am fortunate that she isn,'t here because she might protest the bits and pieces of her life that I want to share with you.

In 1972 she published her autobiography. It is not about chronology but process, and, though the book stops in the year 1972, her process of enrichment has continued.

She was born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1917, and was three years old when her family moved to Chicago. Here she had many homes: 46th and Lake Park, 56th and Lake Park, 43rd and Champlain, among others. And now she lives south of 55th Street on South Shore Drive.

At age seven, she started rhyming words and by eleven was putting poems in notebooks—still in her possession. Her mother told her she would be "a lady Paul Lawrence Dunbar someday. " Her family was warm and supportive, but she chose to be a loner who wrote poetry. She attended high school at Hyde Park Branch, Englewood and Wendell Phillips and then went on to Wilson Junior college. As a young teenager she sent her work to well-known poets, among them Langston Hughes who responded enthusiastically and with whom she remained friends for life.

Later on, when Oscar Brown Jr. helped the

Blackstone Rangers create "Opportunity Please Knock," he asked her to review it. She was so taken by the project that she stayed with the Rangers to help them write and develop it. (Incidentally, 'Opportunity Please Knock" was an exhilarating piece of theater.)

She went on Freedom Rides and slowly realized how deep and unconscious discrimination can be. She notes that even in Merriam Webster's Dictionary it shows up. When you look up the word "black," one of the meanings is given as "opposite of white. " However, when you look up "white", there is no mention of "black." For her, integration then began to mean when Negroes (the educated, professional elite) embraced equally all Blacks (the masses).

Not having an "earned" degree, she now has a whole string of Honorary Doctorates and many other accolades, but the ones she loves come from elsewhere. She speaks about a note from a 16 year old boy who was going to quit school until he heard her recite her poem "We Real cool."

"Now I know there is no place like school, I would want to tell her how I feel inside my heart."

Gwendolyn Brooks never stops growing. In 1971, she flew for the first time and loved it "because it opened up new horizons—being airborne." She speaks with an open heart and doesn't have rules that constrain her. One of her contemporaries says of her, "She is the continuing storm that walks the English language as lions walk in Africa." Her convictions, her strengths and her commitment come out of an exciting and inspiring life.

Ours is an Historical Society and the Cornell Award is intended to confer recognition upon persons who have preserved or extended our understanding and appreciation of Hyde Park's history. Gwendolyn Brooks' contribution has been to give voice and perspective to the story of the African American community which has developed within and become so important to the history of Chicago's south side and to Hyde Park. In the process she has enriched the lives of all of us.

Paul Cornell Awards Committee, 2000

Bert Benade, Chair

Devereaux Bow/ey

Stephen A. Treffman

PARK HOTEL

Exposition, the "artistically arranged flower beds" of

Washington Park, and "the great power house of the Wabash and Cottage Grove Avenue Cable Cars." The latter stood directly across the streec from the hotel on the northeast corner of that intersection. A Chicago City Railway's cable car, clearly marked Number 1597, is depicted heading south on Cottage Grove. It is rumored that the concrete and stone base of the cable car power house still exists on its original site, buried deep under the ground. The hotel itself was demolished during urban renewal in the 1950s. —S.A.T.

Our thanks to Board Member Carol Bradford for bringing us this glimpse of our history IN MEMORY OF EDWIN BURRITT SMITH

After the close of the World's Columbian Exposition, in the mid-1890's, Chicagoans began to look seriously and critically at the social, economic, and political circumstances of their city. They saw a city government whose members were known to enrich themselves at public expense. It tolerated gambling, prostitution, bribery, vote fraud, abuse of patronage, and monopolistic control of public utilities which yielded enormous private profit. The Municipal Voters' League and other organizations were formed in an effort to address these problems. They were part of the larger Progressive movement which swept the country during this time. The reformers also worked to ameliorate the harmful effects of industrialism and business monopolies: urban slums, poverty, and unsafe working conditions.

A Hyde Park attorney, Edwin Burritt Smith, was a prominent and active participant in the reform efforts. At the time of his death on May 9, 1906, a memorial service was held at the University Congregational Church, with tributes from many men who were prominent locally and nationally in the Progressive Movement. The church devoted one entire issue of its monthly newsletter, The Chronicle, to printing the texts of their tributes, excerpts of which are included here.

"He found time to throw himself into those lines of thought, and especially of activity, which Promised to open a door of opportunity to man, which Promised to release at any point the motive and the possibility o fself-growth, and self-government. He did thoroughly and obstinately believe in man...So far as he could choose to have it so, the employment of his Professional Powers was in the interest of a more adequate and abundant life to the individual" Rev. Frederick Dewhurst, the eulogy.

"For, more than upon anything else, his u'hole life centered down upon the welfare of the commonwealth, which called forth all his energies into their most virile expression. In his vision each such struggle as that for the civil service law, for honesty and capacity in city government, for the municipal control of public utilities, for the Peaceful Progress of the nation in the spirit of its constitution and history, and for the social unification of our cosmopolitan people by social settlements and other centers of human equality, was only part of the one great cause of a sane, safe and Progressive democracy. To that greatest cause Mr. Smith devoted the fine abilities and tremendous energies of his life with a generosity and courage, that never seemed to count the Personal cost of his public service. " Letter from Graham Taylor.

Mr. Smith was born in Spartanburg, PA, in 1854. His parents were both teachers who died when he was very young. He spent some of his youth in an orphanage and seemed destined for a life of obscure poverty. Yet his fortitude, vigor, far-seeing hope, and intelligence enabled him to triumph over every obstacle. As a teenager, he was a farm hand, then became a teacher. From 1874 to 1876 he studied at Western Reserve and Oberlin College. After that, he came to Chicago and decided this would be his home. He left to study law at Yale, but after earning his degree in 1880 he returned to Chicago and plunged into his work as an author and teacher of the law. He soon became involved in many of the reform movements which were active in the city during this time.

"He was a giant ofaffairs, a prodigy offacts but his heart was gentleness itself " Letter from John G. Wooley.

He and his wife had two sons, Curtis and Otis. The family lived at 5530 South Cornell and were

active and faithful members of the University Congregational Church, located at 56th Street and Dorchester Avenue.

"His death is a calamity. Few men of my time have brought to the service of the public, such intelligence, such ability, such unselfish devotion, such untiring zeal. Unpopularity had no terrors for him, Preferment no temptations, and when he decided that a certain course u'as right he brought to its support all of his Powers wit/90//t thought ofPersonal consequences. He rendered conspicuous service to his city, to his state and to his country u'ithout asking any recognition for himself... " Letter from Moorfield Storey.

A primary target of the reform effort was Charles T. Yerkes, who held a monopoly of most of the streetcar companies. "With shrewdness, cunning, and force of personality; through continuous stock manipulation; and never without back-door political dealing and bribery, Yerkes constructed a purposely tangled maze of companies that facilitated his kind of large-scale financing. Nor was it happenstance that directly or indirectly he controlled most of the companies that contracted for his projects, nor that those companies' billings were astronomical. Nor that every contractor who did work for him kicked back part of the padded charges." (Johnson, p. 2) Smith was the attorney chosen by the city council to advise it and assist in drafting legislation which would break this abusive monopoly. He was also one of the attorneys chosen by the Chicago Bar Association to investigate the possibility of establishing a separate juvenile court system.

"The list of his civic activities is a history of the better Chicago, not yet a good Chicago, but a vigorous militant demonstration that the great city is the hope of democracy, The earliest step u'as the Passage and adoption of the Civil Service Law. In that movement he was deeply identified. He worked early and hard in the Civic Federation From its inception he was one of the strongest men in the Municipal Voters' League, where his calm courage, his legal knowledge and his power of analysis and statement made him especially terrible to evil doers.... Without hesitation he favored, u'hat some call the 'socialism' of municipal ownership, as an antidote to the 'anarchism' of private ownership as Practiced in Chicago.... The traction problem with its three ugly heads, political, physical and legal, claimed a vast amount of his time and attention. "MR. SMITH AS A CITIZEN" by William Kent.

"The range of his Practice was wide and varied. . ...He was active in litigation involving questions ofpublic interest, the civil service law, the Hyde Park Protective Association, and all are familiar with his recent activities as special council for the city of Chicago in the important traction litigation u'hich seems now to be drawing to a close. "

"MR. SMITH AS A LAWYER" by Judge H. V. Freeman.

"Chicago IC'as in a fierce struggle for better transportation—her citizens for overforty years had been struggling against odds to free themselves from what they felt was an unrighteous claim by the companies—a comprehensive study of the Practical and engineering problems had been made by the Council. The Committee having the subject matter in charge required legal advice of high order to guide it in negotiation and in Putting in legal form the conclusions reached... (it) began to look about for a man.....Mr. Smith was selectedfor this important position.

"MR. SMITH'S SERVICE TO THE CITY" by Frank I. Bennett

"It is Pleasant to think that, although Mr. Smith's activities touched the u'hole life of the city, and in many cases the interests of the nation, this church and community were his home. He belonged especially to us. And here will be his memorial.

"MR. SMITH'S RELATION TO THE CHURCH" by Prof. A. H. Tolman

In his memory, a stained glass window depicting the Old Testament Prophets was placed in the wall of the church. This window is now placed in the Rittenhouse Chapel of the United Church of Hyde Park.

B I B L I OG RAPHY

Block, Jean. Hyde Park Houses. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978, pp. 60-63.

The Chronicle of the University Congregational Church, Chicago. vol. Il, No. 5. May 1906.

Johnson, Curt. Wicked City Chicago: From Kenna to Capone. Highland Park: December Press, 1994.

Lindberg, Richard. Chicago Ragtime: Another Look at

Chicago, 1880-1920. South Bend: Icarus Press, 1985. Spinney, Robert G. City of Big Shoulders: A History of Chicago. DeKaIb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2000.

Tanenhaus, David S. "Justice for the Child: The Beginning of the Juvenile Court in Chicago" in Chicago History, Winter 1998-99, Vol. xxvll, No. 3, pp. 4-19.

A WORD FROM OUR PRESIDENT

Alice Schlessinger

A NEW PROJECT FOR THE SOCIETY

Last year, through the good offices of Representative Barbara Flynn Currie, we received a grant of $2,500 to help us start a project in aid of education for our community's school children. We used the money to set up a web page, with the hope that it could provide access to our archives for those who are studying community history. You may see this page by going on the internet and looking up www.hydeparkhistory.org.

This year we are to receive $5,000 from Senator Barack Obama and Representative Currie. With these additional funds we are launched on working with the schools. We've started with Ray School. We have met with the computer teacher at Ray, and spoken with the principal there. Our method is to offer help to teachers whose curriculum includes study of the community—third and eighth grades. With the assurance that we shall receive our full funding, we are planning to expand our pilot project to Brete Harte and Murray Schools and to Kenwood High School. In the future we will expand to all the schools in our community.

We hope that this project will result in an interactive exchange—we can provide the information about the fascinating history of this community. We hope that the students will post material from their work on our page, so that others, all around the world, will be able to see what our students can do. We also expect that information will flow in both directions as a result of this effort.

We are very grateful to Barbara and Barack for their help in getting us started on this exciting step in making the archives and newsletters of the Society available to the young people of our area, and in strengthening the bond between us.

WORLD WAR Il AND HYDE PARK

Memories and artifacts of Hyde Park during World War Il would be of great interest to us. That was an intense period and if any of our readers who lived in Hyde Park during that period would like to share their memories, we would like to have them. What was Hyde Park like in those days? What changes in Hyde Park occurred during the War? Write us a letter and tell us about your experiences during that period. We are also seeking Hyde Park memorabilia from that period. —S.A.T.

A CABLE CAR TRAINMAN—a burly bearded grip man, bundled in a thick fur coat and gloves against the harsh wintry elements. This steel engraving by T. de Thulstrup, appeared on the cover of the February 25, 1893 issue of Harper's Weekly. It is hard to judge, but the passengers appear to be either miserable or, as dutiful Hyde Parkers, deep in thought. Life was not easy in those days.

Volume 23, Number 2

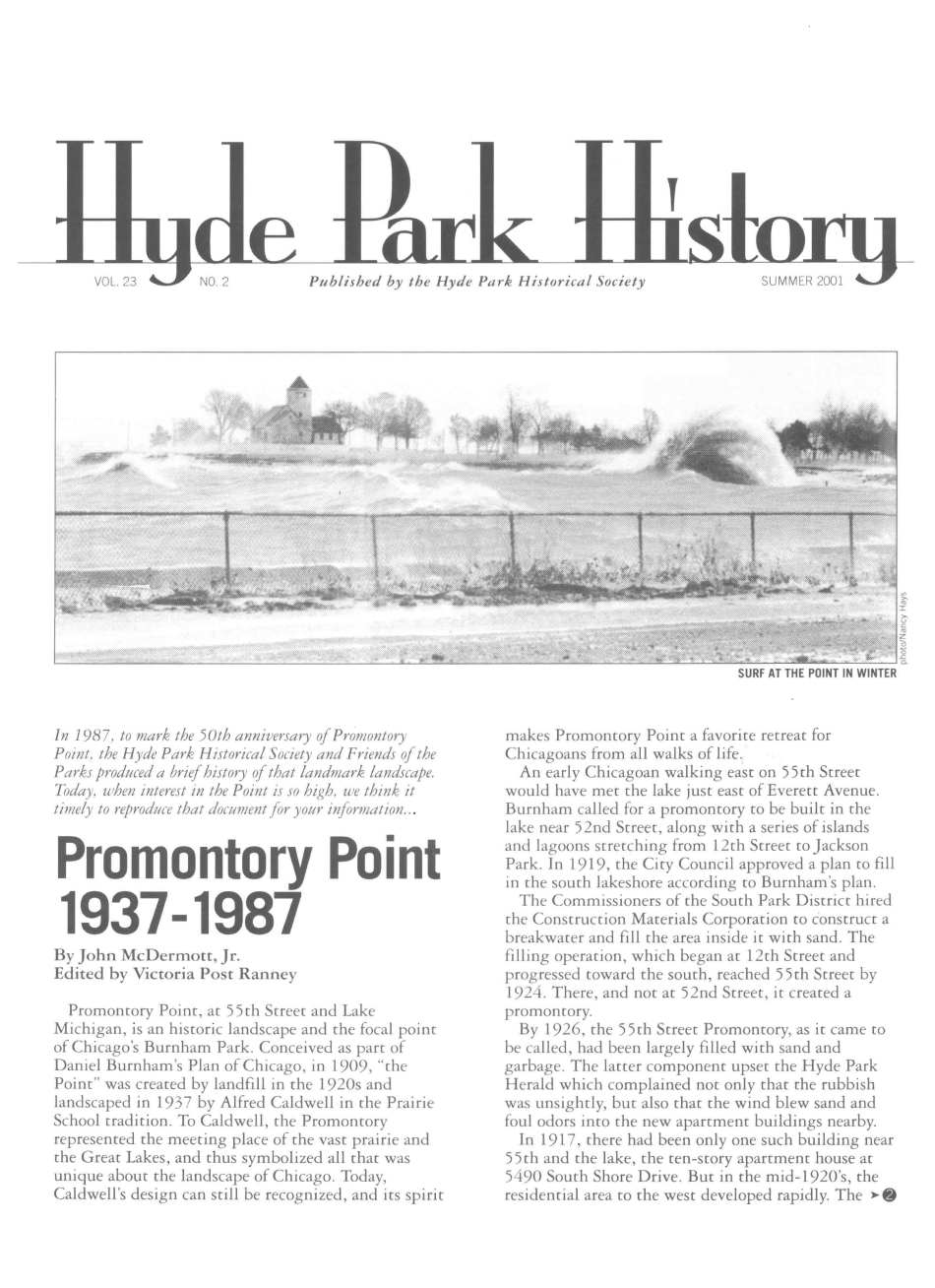

In 1987. to mark the 50th anniversary of Promontory Point. the Hyde Park Historical Society and Friends of the Parks produced a brief history of that landmark landscape. Today. when interest in the Point is so high. we think it timely to reprod11ce that dowwent for yot1r information...

Promontory Point

1937-1987

By John McDermott, Jr.

Edited by Victoria Post Ranney

Promontory Point, at 55th Street and Lake Michigan, is an historic landscape and the focal point of Chicago's Burnham Park. Conceived as part of Daniel Burnham's Plan of Chicago, in 1909, "the Point" was created by landfill in the 1920s and landscaped in 1937 by Alfred Caldwell in the Prairie School tradition. To Caldwell, the Promontory represented the meeting place of the vast prairie and the Great Lakes, and thus symbolized all that was unique about the landscape of Chicago. Today, Caldwell's design can still be recognized, and its spirit makes Promontory Point a favorite retreat for Chicagoans from all walks of life.

An early Chicagoan walking east on 55th Street would have met the lake just east of Everett Avenue. Burnham called for a promontory co be built in the lake near 52nd Street, along with a series of islands and lagoons screeching from 12th Street co Jackson Park. In 1919, the City Council approved a plan co fill in the south lakeshore according co Burnham's plan.

The Commissioners of the South Park District hired the Construction Materials Corporation co construct a breakwater and fill the area inside it with sand. The filling operation, which began at 12th Street and progressed coward the south, reached 5 5ch Street by 1924. There, and not at 52nd Street, it created a promontory.

By 1926, the 55th Street Promontory, as it came co be called, had been largely filled with sand and garbage. The latter component upset the Hyde Park Herald which complained not only chat the rubbish was unsightly, but also that the wind blew sand and foul odors into the new apartment buildings nearby.

In 1917, there had been only one such building near55th and the lake, the ten-story apartment house at5490 South Shore Drive. Bue in the mid-1920's, the residential area to the west developed rapidly. The huge Shoreland Hotel was completed in 1926, and the Flamingo opened in 1927. These buildings began a wave of hotel growth that eventually provided 20,000 rooms in East Hyde Park.

By 1929, grass was planted on the Promontory. Leif Erickson Drive (now Lake Shore Drive) was opened to traffic and trees were planted on the portion of landfill west of the Drive. But construction did not proceed until the consolidated Chicago Park District was formed in 1934. At about that time, Fifth Ward Alderman James Cusak began to receive complaints that the Promontory was being used as a makeshift parking lot by the nearby Shoreland Hotel. In an interview shortly before his death in 1986, Cusak said that he had used his influence with the Park District's new general superintendent, George T. Donoghue, to have the parking lot removed and the Promontory developed.

Whether or not Cusak's influence played a role, the

Promontory, in 193 5,was designated to receive funds and workers from the Works Progress Administration. It was one of 67 Illinois parks which the WPA assisted during the Depression. Thanks to the WPA, the Point was developed as we know it today.

The planning was assigned to Alfred Caldwell, an architect and landscape architect on the Park District staff. From 1926 to 1931, Caldwell had assisted Jens Jensen, the great landscape architect of Chicago's West Park system and the pre-eminent figure in the Prairie School movement in his field. Caldwell shared Jensen's devotion to the midwestern landscape and his practice of using only native plants in his parks.

Caldwell began by adding soil, raising the meadow to its present height and creating a hill where a shelter would be built. By the summer of 1936, water and sewer pipes had been laid, and the underpass below the Drive was completed.

Caldwell's planting plan, dated September 1, 1936, relied on indigenous plants. It included 241 American elms, 50 American lindens, and 637 prairie crabapples, as well as sugar maples, hop hornbeams, and two varieties of hawthorn, the tree which had been one of Jensen's trademarks.

The thick groves of trees and shrubs formed a ring around a large central meadow which sloped downward gradually toward the path. The ring was interrupted at the north, allowing a spectacular view of the downtown skyline, and at the south, where the vast manufacturing districts of South Chicago and Indiana were visible on the horizon. The Point includes two distinct experiences: the lofty meadow, from which the rocks along the water cannot be seen, and the rocks themselves, from which the meadow cannot be seen. Plantings on the outer edge of the peninsula once reinforced this distinction.

Caldwell said in a 1986 interview that he had conceived of the Promontory as "a place you go co and you are thrilled-a beautiful experience, a joy, a delight." He sought co convey "a sense of space and a sense of the power of nature and the power of the sea."

A member of the Park District's architectural staff,

E. V. Buchsbaum, designed the shelter (now known as the fieldhouse). Construction began in 1936 and was finished the next year. The walls were made of Lannon scone, quarried in Wisconsin. Caldwell, an architectural modernist, tolerated the building though he felt it was coo heavy for the site and of little architectural value. Buchsbaum felt he was creating a "picturesque, distinctive building" and that its playful allusion co a castle or a lighthouse were appropriate for the setting.

After 193 7, the area received various small improvements. Benches were erected in 1938. Boulders called for in Caldwell's plan were set in place in March, 1939. Also in that year, the David Wallach Memorial, a bronze sculpture of a resting fawn set on a marble fountain, was dedicated. Little is known about David Wallach who, at his death in 1894 left a bequest for a fountain in a park for "man and beast." True co his wish, the monument has a drinking fountain at ground level which has been enjoyed by generations of local beasts.

In the late 1930's and 40's, the Shelter became a busy center for square dances, scout meetings and other activities. In 1953, the U.S. Army leased land from the Park District for a Nike missile base on a Jackson Park meadow. Soon afterward, it cook pare of the Point for a radar site. The towers stood south of the fieldhouse on a large tract surrounded by a barbed wire fence. One of the cowers reached 150 feet in height, and all of chem dwarfed the turret of the fieldhouse.

Many neighborhood residents resented the radar cowers, but protests became vocal only in the Vietnam era. After the cowers finally came down in 1971, there was a victory rally with the slogan, "We've won our Point!"

For its 50th anniversary in 1987, a group of landscape architects carefully surveyed the Point, comparing the original features executed under Caldwell with the landscape of today. Though few of the original shrubs and trees remain, and lake damage has badly_eroded the perimeter, the basic features and open spirit of the design can be seen. Park District officials and the public, recognizing the place of Promontory Point in Chicago's past and its value in the present, should work co restore, for future generations, chis historic prairie landscape on the lake.

PHOTOGRAPHS AND FILMS SOUGHT

Beach Street Educational Films is making a movie about World War 11 servicemen who were refugees from Germany and Austria during the 30s and 40s. Because Hyde Park received many of these refugees, the film makers have asked the Society for help. Julia Rath, producer of the film, would like to have pictures from that time of any such refugees who served in the armed forces during the war. You can reach her at 847-677-6018, or email at JWRath@netzero.net, if you have questions.

ABOUT ALFRED CALDWELL

By Stephen A. Treffman

Alfred Caldwell, the landscape designer of Promontory Point, was a poet, landscape architect, civil engineer, city planner, philosopher and distinguished professor. He was born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1903. lo 1909 his family moved to Chicago. He attended Ravenswood Elementary School and Lake View High School, where he became fascinated by the study of botany and Latin. After a brief but unhappy stint in the landscape architecture program at the University of Illinois, Caldwell managed to land a job in 1924 as an assistant to Jens

J eosen, the highly respected Chicago landscape architect. Jensen would ultimately characterize Caldwell as a "genius." In 1927, Caldwell befriended and was profoundly influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright.

The onset of the Depression broke up Jensen's firm and from 1931 to 1934, Caldwell was in private practice as a landscape architect. From 1934 to 1936 he served Dubuque, Iowa as its Superintendent of Parks and created the renowned Eagle Point Park there. He returned to Chicago in 1936 to join the Chicago Park District as a landscape designer. It was during this period that he worked out the design for Promontory Point and planned the Lily Pool and Rookery in Lincoln Park. lo the course of this work he met Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who later played a major role in the evolution of Caldwell's-career.

Caldwell left the Park District to join the U.S. War Department in 1940 and worked as a civil engineer on the design and construction of several military training posts. At the end of the war, Mies called upon Caldwell to join the architecture faculty at the Illinois Institute of Technology. In 1945 IIT awarded

Caldwell a Bachelor of Science degree in Architecture and, in 1948, a Master of Science degree in City Planning. His major collaborative work with Mies was as the landscape designer for the UT campus. He abruptly resigned from IIT in 1960 in protest of Mies' ouster as official architect of the school.

From 1960 to 1964 Caldwell was employed by the Chicago Planning Commission. He returned to higher education as a Visiting Professor at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute in 1965 and later that year was appointed Professor of Architecture at the University of Southern California, retiring in 1973. He maintained a private practice until 1981 when he rejoined IIT as the Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Professor of Architecture. Proclaimed the last of the Prairie School landscape architects, he died at his home in Bristol, Wisconsin in 1998.

Caldwell's plans for the landscaping of PromontoryPoint were very precise. Each tree and shrub was carefully located and designated by its proper Latin. name. Not usually recognized is that his plans included not only the area popularly considered the Point, that is, the land east of the South Outer (Leif Ericson) Drive at 55th Street, but also the park areas on the west side of the Drive from about 5450 to

5555 South Shore Drive. Parenthetically, it is at 5530- 32 South Shore Drive that the Mies designed, and aptly named, Promontory Apartments now stands.

Although many changes in the landscaping in this area have occurred since Caldwell's day, a few trees surviving from his original planting some 65 years ago can still be found, the largest number of them probably along South Shore Drive. The lake has undermined

the base of the limestone revetment around the Point to the extent that, at some spots, gaps large enough to

swallow a small child have emerged between some of the seawall's stone blocks. llli1

Sources on Caldwell: The standard source, including an extensive bibliography, is Dennis E. Domer, ed., Alfred Caldwell: The Life and Work of a Prairie School Landscape Architect (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1997). Darner's obituary for Caldwell may be found in the IIT Catalyst (Summer, 1998). See also Werner Blaser, Architecture and Nature: The Work of Alfred Caldwell (Basil and Boston: Birhauser Verlag, 1984). The Art Institute of Chicago library has a transcript of a lengthy interview conducted with Caldwell.

Looking Back A Bit...

May. 1888

HARPER'S NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE

"Studies of the Great West - Chicago"

by Charles Dudley Warner,

Washington Park, with a slightly rolling surface and beautiful landscape gardening, has nor only fine driveways, bur a splendid road set apart for horsemen. This is a dirt road, always well sprinkled, and rhe equestrian has a chance besides of galloping over springy turf. Water is now so abundantly provided that the park is kept green in rhe driest season. From anywhere on the south side one may mount his horse or enter his carriage for a turn of fifteen or twenty miles on what is equivalent to a country'road, that is to say, an English country road.

On the lake side of the park are the grounds of the Washington Park Racing club, with a splendid track and stables and other facilities which, I am told, exceed anything in the country of the kind. The clubhouse itself is very handsome and commodious, is open to members and their families summer and winter, and makes a favorite rendezvous for that pare of society which shares its privileges. Besides its large dining and dancing halls, it has elegant apartments set apart for ladies. In winter its hospitable rooms and big wood fires are very attractive after a zero drive.

The city is rich in a few specimens of private houses by Mr. Richardson ...so simple so noble, so full of comfort, sentiment, unique, having what may be called a charming personality. As to interiors, there has been plenty of money spent in Chicago in mere show, but, after all, I know of no other city that has more character and individuality in its interiors, more evidences of personal refinement and taste due, I

imagine mainly to the taste of the women, for while there are plenty of men who have taste, there are very few who have the leisure to indulge it.

Along the Michigan Avenue water front and down the lake shore to Hyde Park, on the Illinois Central and the Michigan Central and their connections, the foreign and local trains pass incessantly (I believe over sixty a day)...and further down, the tracks run between Jackson Park and Washington Park, crossing at grade the 500 feet wide boulevard, which connects these great parks and makes them one.

These tracks and trains... are a serious evil and

danger, and the annoyance is increased by the multiplicity of street railways and the swiftly running cable cars, which are a constant threat to the

tim_id....In time the railroads must come in on elevated viaducts...

September 24. I 942

HYDE PARK HERALD

At last, it has happened! The Chicago Beach Hotel, probably the most famous of Chicago's many hostelries, has been commandeered by the U.S. Government for use as a base hospital. Federal Judge Michael Igoe signed a court order which was served upon the hotel corporation yesterday authorizing the

U.S. Army to take possession. Meantime Stephen Clark, manager of the hotel, is organizing an information bureau for the benefit of guests who must seek new housing. The 300 families will have about 30 days in which to find accommodations.

Many have been living in the hotel since it was opened in 1920 and others were occupants of the original Chicago Beach Hotel, built in 1893 and razed after the present building was completed.

October 14. 1887

HYDE PARK HERALD

Weather permitting, the Nickle Plate baseball nine plays with the Pullman's Plate nine tomorrow afternoon on the latter's grounds. The Herald wishes to inform rhe Nickle Plate nine, that if they want to be fortunate again in having ladies as spectators at any of their future games, that they should cease their profane and disgraceful language while in the field, as they used while playing the Prairie Kings last Saturday, at which occasion a number of ladies were present. If you desire the interest of the people you must act like gentlemen.

Volume 23, Number 3, Published by the Hyde Park Historical Society, FALL 2001

HYDE PARK AT THE BEGINNING OF WORLD WAR Il: CAMPUS REMINISCENCES

By Yaffa Claire Draznin

Every memoir is inevitably a Rashomon narrative, more revealing of the teller's perspective than of history as it really happened. This recollection of the experiences my husband Julius and I had as students on the Chicago campus is no exception. Admittedly it only covers about three years, from early 1941 until August 1944—and is selective, with no discussion of faculty activity (about which we knew nothing) nor administration plans for the new B.A. plan, nor activities in the greater Hyde Park community. No matter: this is our story.

1941. We came on the campus separately. Julius drifted onto the campus in early 1941, having attended Wright Junior College for a year and subsequently joining the American Friends Service Committee in its work camps throughout the Midwest. He hung around, as he tells it, seeking out guys he knew from Tuley High, and at some point decided to became a student himself. After passing the entrance exam but with literally no money at the time, he got his education by the "low cost" method permitted then, by enrolling for as many courses as he could afford and studying independently (following the syllabus without actually attending classes), taking only the final exam that determined his grade. (He was finally admitted for both undergraduate and graduate courses in January 1942.)

Since he had helped start cooperatives among field workers and sharecroppers while with the Friends, he looked for, and joined, the men's housing co-op at 52nd and Ellis. My introduction to the U. of C. in early '41 was more conventional. I came to Chicago as a transfer student from the University of Wisconsin and went directly into the political science division, while taking up residence in a university owned and tightly supervised off-campus facility for female students in the 5800 block of Drexel.

It was an ominous time, those months before Pearl Harbor, although it's hard now to fully recapture the urgency and anxiety that laced our lives then. The horrendous news from Europe, now totally overrun by the Germans, had us glued to our radios deep into the night, and we woke each morning to broadcasts from London. On hearing Edward R. Morrow and Charles Collingwood describe the devastation from the Luftwaffe bombs that had rained down upon it the previous night. Our days were filled with continuous, contentious bull-sessions on the morality and ramifications of the war and whether the U.S. should declare war on Germany. (Japan, known only as an Axis partner, was hardly given a thought.)

Campus politics in those days reflected a conflicted nation and opposing political messages, with the America-First isolationist sentiment being espoused despite (or perhaps because of) the gradual and increasing shift in our national economy to a war footing, to provide lend-lease aid to Great Britain, the remaining unoccupied democracy in Europe. As students we knew of the concentration camps but were unaware then, as was the nation, of theif eventual horrific purpose as death camps and of the Final Solution planned for the Jews of Europe. We were equally unaware of the secret research going on in America, especially on our campus, in the field of nuclear fission, eventually leading to the development of the atomic bomb.

We (our crowd) were generally anti-war activists of the Socialist Party, rallying around that popular social science instructor Maynard Krueger, the vice presidential candidate on the Socialist Party ticket headed by Norman Ähomas. Of course, we insisted that our pacifism was different from the vitriolic isolationism of Charles Lindbergh and the America Firsters, and as it happened, even our university president, Robert M. Hutchins, was vehemently antiwar. Early in 1941, according to the Daily Maroon, he appeared on the American Town Hall of the Air, with Col. William Donavon (later of OSS fame) to debate the question, "Should we do whatever is necessary to insure a British victory?" Hutchins took the negative position. The paper didn't say who won the debate.

But we had no difficulty separating ourselves from the pro-Communist fellow-travelers of the American Students Union who, up until June 22, 1941, were also vitriolically against the war in Europe ("The British are as fascist as the Germans and Italians!"). But in a single day after that date, when the Germans invaded the Soviet Union, the organization made a 180-degree about-face and changed its line in the blink of an eye to rabid support of every war preparedness effort taken or envisioned, denouncing any labor union which even contemplated strike action, screaming "Defeat Fascism" with abandon.

But while we talked and argued about the war constantly, more mundane living adjustments occupied much of our time. The high cost of living was a pressing constant for those of us on limited

budgets and many of us happily became part of what was then a growing student cooperative movement, seen as one solution to the problem of finding affordable room and board.

In 1941, a two-story stone building on the northwest corner of 56th and Ellis already housed an eating cafeteria on the ground floor, a consumer cooperative governed by the democratic Rochdale Principles. There students could, after paying a minimum membership fee, eat lunch and dinner at prices cheap enough to fit into even the most skimpy living allowance.

On the second floor of that building was the Ellis Housing Co-op, also a consumer cooperative, which men (only) could join and rent a single or double sleeping room for very low cost. (In a Maroon article in 1943, Ellis Co-op rents were quoted as from $8.50 to $11.50 a week; in '41, they must have been less.)

A third cooperative four blocks to the north, at 52nd and Ellis, the University Housing Co-op, provided more housing for men. Julius lived there, tending the furnace and doing houseman chores in exchange for a free room.

Sometime in the spring or summer of 1941, a group of women decided it was their turn. With the ready assistance of the men from both housing co-ops (not an insignificant incentive), they organized a women's housing Co-ops heard about the group after the initial planning and furniture accumulation was already done —but did manage to be in the first group of women who moved into Woodlawn House at 5711 Woodlawn that fall. As such, we made long since-forgotten history by not only founding the first women's co-op on campus but, after the first quarter, becoming the first women's housing available on the University of Chicago campus run sans housemother.

In 1941, men were registering for the peace-time draft, faculty members were leaving for Washington for duty with the newly formed defense agencies, and refugee celebrities from Europe flooded the campus, to lecture and to work/ beg, exhort us all to save their shattered compatriots in Europe. One such was Jan Maseryk, the son of the man who founded Czechoslovakia in the 1920s, who, having escaped the Nazis, became a political science lecturer on campus. (NVhen the war ended, he returned triumphantly to a free Czechoslovakia and was elected president of the country, only to have his country invaded by the Russians and he himself murdered by the Communists, who replaced the Nazis in occupying his country in post-war Europe.)

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 and the declaration of war against Japan and its Axis partners, Germany and Italy, stunned us all. From then on, our lives were irrevocably altered.

1942. The exodus of men from the campus became precipitous that year, as draft boards called draftees up for military service. In spring 1942, four of us students traveled to the University of Minnesota as delegates to a student co-op conference where, unexpectedly, I was elected president of the newly formed Midwest Federation of Campus Cooperatives. This had nothing to do with my sterling qualifications but came about because the men decided that, since they were off to war, some woman or other had better take over.

Surprisingly, a fairly large contingent of men were still around, not called up by the draft —and some fifteen or more of them lived in the University Co-op where Julius had a room. My husband-to-be was generally too busy to take much notice of their activities since, besides carrying a full academic load and working as co-op houseman, he also worked as a night watchman at Michael Reese. But it was fun to speculate what kind of job those guys were doing down at the physics labs (they were absolutely mum about it) because, as he told me, they used to come home looking like coal miners, their clothes covered with what looked like layers of carbon and graphite. The last was the operative distinction. As we later found out, they were constructing graphite bricks for the atomic pile.

My husband and I became engaged late that spring, holding off marriage plans until he heard the results of his draft physical. When in early 1942 Julius was rejected for active service (because, as he himself knew in depressing detail, he was still suffering regular attacks from an active seven-year malarial infection he had contracted while with the Friends in southern

Missouri), we set our marriage for late December 1942.

The war was now an integral part of campus life, the visible armed forces in the Quads seeming to multiply geometrically. Soldiers in crisp tan uniforms marched about, singing in cadence, members of the ASTP (Army Specialized Training Program), being trained (we found out later) for language and engineering tasks to be used on some unspecified duty in Europe during or after the war. Sailors were also everywhere; according to the Daily Maroon, some 600 of them, signal corps trainees, were being bunked in Sunny Gym and fed, en masse, in the Ida Noyes Cloister Club.

Buildings were being renovated in odd and obscure ways. Eckhart Hall had had a double stairway leading up to the second-floor library, but suddenly, one day, only a single staircase was visible, climbing to the floor above. On the other side, where a stairway should have been, was simply a wall, the same color as the other, showing signs of wear and student fingermarks along it —except that it hadn't been there the week before. Ryerson was also off limits, more or less. An article on the history of Ryerson Hall in the Maroon mentioned vaguely that its Physical Laboratory was being used by the army for experimental purposes, and a librarian was quoted as saying she couldn't get near the place to get some books she needed.

In the summer of 1942, while Julius was taking classes, working on an NYA work-study grant and mopping floors at the eating co-op, I took a job in the defense industry, traveling to the Western Electric plant on 22nd and Cermak, which had stopped making telephones and started making radios for the Navy. As an inspector of radio condensers that came off an assembly line, I received the princely wage (almost twice that of the solderers on the line) of 5 1 cents an hour.

Julius's NYA job turned out to be the instrument that breached the tightest security system on the campus. He was working for Buildings & Grounds at the time, B&G being the department that took care of everything mechanical and nonacademic on the campus, including campus policing. On a day when the head janitor was out of the office, a phone call came through about a fire in one of the dorms.

Someone shoved a piece of paper into his hand with the janitor's name on it and told him: -"Go find this man, and fast!"

Hurrying from one building to another, Julius entered Eckhart where, after checking through empty halls, he spotted a door off on the side. There was no one about. Facing a stairwell he followed it down into a sub-basement, stepping out into what appeared to be a laboratory, with tables of equipment. At one of the tables, looking at him in shock and horror, stood one of his co-op housemates.

"What are you doing here!" the man said. "Who let you in? Nobody's allowed down here!"

Apparently the unlocked door he had passed through led into the security Holy of Holies, the labyrinth of halls, labs and rooms that ended up under the west stands of Stagg Field where, on December 2, 1942 (as we learned much later), a group of young physicists, including many from the co-op, leaned against the walls sipping lab-distilled grain alcohol from paper cups, toasting each other and the occasion, and shared with Enrico Fermi a quiet celebration of the birth of the first controlled, sustained nuclear reaction.

1943. Once we were married, we moved out of our respective co-op houses and set up housekeeping in what passed for neighborhood student housing, first on Maryland Ave. (communal bath and toilet in the

hall, 2" cockroaches in the kitchen), then on 55th and Blackstone (listening to the one-nighters scream obscenities at each other on the stairs). We continued to eat most of our meals at the Ellis Co-op where we were regularly reminded to turn in our sugarrationing and meat-rationing food stamps, since food couldn't be bought without them.

That spring, my husband became the co-op's fulltime paid manager and spent every minute he could (when not thinking of class work), trying to keep the operation afloat, worrying about how to pay the help and buy food with few funds. The number of paying students plummeted with the shrinkage of men on campus —and by summer the co-op could no longer keep operating. It was Julius's unhappy duty to shut it down: selling the furniture, the kitchen equipment, the #10 cans of tomatoes and carrots that had accumulated in the basement, the lot. What money was finally salvaged was put into a trust fund supervised by willing faculty members (Maynard Krueger was one), later used to help new co-ops get started after the war.

The male-drain became especially noticeable among the faculty in 1943. As a political science student, I remember that, in the last two terms before I graduated, the department was literally denuded of instructors. Of the eight courses I took, only one was taught by the instructor listed in the catalog. All the rest were foisted on Prof. Jerome Kerwin who stepped in to teach them all (for which I was extremely grateful), after the designated instructors left for Washington or the armed forces.

After graduation in 1943, I became co-breadwinner and looked around for work. My only nonacademic skill being typing, I first took an office job at the Central States Cooperative (the regional distributor to the eight or more consumer cooperative groceries in the Chicago area) and then, closer to campus, at "1313" across the Midway with the American Public Works Association, earning a normal typist salary, about $25 a week.

In the fall of 1943, with the luck of the nonlrish, we were accepted as members of Concord House, one of the most unusual and exciting experiments in cooperative living in Hyde Park.

The house was a majestic three-story Victorian mansion, with grounds, at 5200 S. Hyde Park Blvd. (where Rodfei Zedek Congregation now stands). It had a magnificent living room with a fireplace, a large dining room, and full institutional kitchen, with dozens of sleeping rooms. A Dr. Jay Jump, a dentist, was the directing force in the House; he may even have been the actual owner of the property, with the co-operative renting on a long-term lease.

The governance of the House was, again, based on the consumer-cooperative Rochdale Principles: democratic control, nondiscrimination in all areas but especially in terms of race and politics, and a cooperative sharing of household chores and financial responsibilities. All members, students and nonstudents alike, were accepted through a vote of the residents.

I seem to remember only one paid employee, the cook; but I wonder whether we didn't also pay someone to be the administrator of what was a rather complicated room-and-board arrangement. While each person was responsible for her or his own sleeping quarters, the cleaning of the communal areas, food preparation, laundry, and house-operating chores were shared by all the residents, allocated among them through a complicated and detailed work schedule, rigorously enforced. Among the jobs on the work schedule was the planting, weeding, and tending of a huge Victory Garden plot at the north end of the block (near the Fifth Army headquarters) that furnished the bulk of the vegetables ending up on our dinner table.

As part of the Hyde Park community, we participated in all the civil-defense activities required. We turned in our sugar and meat food stamps, collected flattened tin cans, saved congealed beef and bacon fat for use in the manufacture of munitions, and participated in the regular citywide air raid drills. When the citywide sirens went off, we all were told to pull down the window shades, put out all lights, and gather on the ground floor near the stairs to the basement, earlier prepared for use in the eventuality of a bombing. Many of us regarded it as a lark, and a contingent of pacifists living in the house were reluctant participants; but the two European refugees living in the House at the time, Bert Hozelitz and Fred Lister, were designated Air Raid Wardens in charge of the exercise. They had had enough bitter personal experience with war to insist, with vehemence, that we obey the routine to the letter. And we did.

1944: In spring, my husband was notified that his job application to the National Labor Relations Board was being considered—and from then on. we existed, in penury but with hope, that an appointment would soon come through.

By then it was obvious that my office job wasn't earning us enough to cover our expenses. Finding that war work paid higher wages, I took a job at Carnegie Illinois Steel in South Chicago. Despite the asphyxiation-level of hydrogen sulphide (the "rotteneggs" odor) that inundated the steel mills, the pay was generous. At first I was assigned a job in a labor crew, shoveling sand out of box cars (at 63 cents an hour), one of a contingent of women being hired at the mill. (In World War I, black men finally broke the job barrier in the steel industry; in World War Il, the same thing happened for females, white or black.) I was the only Anglo among a crew of 15 Hispanic women sand-shovelers but eventually, possibly because of my conspicuous presence, someone decided that I might be better used elsewhere. I was promoted to work in the chemistry lab and paid $1.03/hr.

Concord House in 1944 came under heavy community censure because of our nondiscriminatory admission policy. The local Chamber of Commerce was unremitting in castigating us for lowering property values by admitting nonCaucasian to live there.

We also were seen as a subversive element because of the large number ofJapanese-Americans who lived in the House. Many apparently had heard about Concord House while still in internment camps and, after they were released, came to live with us for a while before making more permanent plans elsewhere.

In late summer of that year, Julius was notified that he was accepted as an entry-level professional field examiner for the NLRB (at the munificent salary of $2,000 per annum) and we left the campus in August, 1944, for his government assignment in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

MY FIRST TRIP

TO HYDE PARK

By Carol Bradford

My family always took a vacation in August, after the oat crop was harvested and before school started. Often we went to Duluth, Minnesota, where my father could get relief from hay fever. Other times we went west to the Black Hills or to Colorado, where my mother had a cousin. But in 1957 we broke with tradition and went east for the first time.

We left our South Dakota farm early on the morning of August 15. My father drove 'our 1952 Ford across Iowa. We stopped en route to visit relatives and then went on to Dubuque. There we visited the University, where my grandfather had attended seminary and I later attended college. The next day we drove to Chicago, spending the night at a motel in one of the western suburbs.

My parents' diary for Saturday, August 17 reads

"Very nice in Chic, went to airport, went thru big French plane, saw amphitheatre, stockyards. Most of day in museum. Took boat ride on lake tonite." Was that a busy day or what? As usual, my parents had checked AAA guidebooks and other sources and decided what they wanted to see in the city. We stopped first at Midway Airport. I don't know why we didn't go into the terminal, but we did stop at an Air France hangar off Cicero Avenue and saw some of the large planes there. We probably went straight east on 55th Street, making a stop along the way at the stockyards area, and then on to the Museum of Science and Industry.

What an awesome place it was for all of us! My brother, David, a year younger than I, and my sister Nancy, 8 years old, were fascinated with everything. We went to the coal mine, the submarine, and all the other exhibits. "Yesterday's Main Street" was a favorite and of course we had to get our picture taken on the antique car. I was thrilled to find that picture once again a few months ago among my parent's many photo albums.

That night we stayed at one of the old Hyde Park hotels. How I wish that my parents would have written down the name of it in their diary. I remember it as a dark building, not far from the Museum. We had a room with a Murphy bed, which I had never seen before.

We stayed in Chicago three more days. We got a

I

room at the Hamilton Hotel downtown, which had been recommended to us by a friend in Dubuque. We went to the Aquarium, the Board of Trade, the Merchandise Mart, Buckingham Fountain, and the top of the Prudential Building (which was the tallest in the city at that time). We shopped on State Street and rode the Ravenswood "el" to the end of the line and back downtown. On our last afternoon, we went to a White Sox double-header against the Washington Senators. We left shortly after the start of the second game, so as to get a good rest before starting home the next morning. Later, we learned that we had missed a no-hitter, won by the Senators.

On August 21, we left Chicago at 5:15 A.M. We drove west on Highway 30 across Illinois and Iowa. From Chicago to our home is a distance of about 600 miles. By 6:30 P.M. we were back in South Dakota at the home of my older sister, Helen, who had just married earlier that year. We stopped there to celebrate her birthday.

I didn't imagine during that trip that I would spend most of my life in Hyde Park, but I will always cherish the memory of that first special visit here.

This Newsletter is published by the Hyde Park Historical Society, a not-for-profit organization founded in 1975 to record, preserve, and promote public interest in the history of Hyde Park. Its headquarters, located in an 1893 restored cable car station at 5529 South Lake Park Avenue, houses local exhibits. It is ooen to the public on Saturdays and Sundays from 2 until 4pm.

Telephone: HY3-1893

President Alice Schlessinger

Editor Theresa McDermott

Designer. Nickie Sage

Regular membership: $15 per year, contributor: $25 sponsor: $50, benefactor: $100

If you have access to the internet, our society's newly created website can be found at www.hydeparkhistory.org.

Volume 23, Number 4, Published by the Hyde Park Historical Society, WINTER 2001-2002

MY SCHOOL DAYS IN HYDE PARK

HPHS President Alice Schlessinger, formerly editor of LAB NOTES, U-High'sJournal, has suggested that Society members might be interested in the recollections of Pan/ H. Nitze, class of 1923, recollections he wrote for that journal in 1985.

In 1910 my father was asked by President Harper to join the faculty of the University of Chicago as head of the Department of Romance Languages and

Literature. We moved from Berkeley, California, to the Del Prado Hotel on 59th Street, on the lakeshore side of the Illinois Central Railroad tracks, in the fall of that year. I remember it as being a glorious place with high ceilings, sunny rooms, an enormous veranda with rocking chairs.

I was three; I had a friend who was four and much more grown up. I admired him immensely. Emily Kimborough, in her book about growing up in Chicago, has an amusing description of us staying at the Del Prado Hotel—the Nitze family, their charming daughter Pussy, and their spoiled, objectionable brat of a son. I am sure she reports accurately. Pussy was in second grade in the elementary school while I was being a pest around the hotel. The next year we moved to a house on what was then Blackstone Avenue between 57 th and 58 th Streets.

That summer our mother took us to Fish Creek,

Wisconsin, to escape the heat of the Chicago summer. We drove up with the Guenzels, friends of my parents, in a glorious red Stanley Steamer. The roads north along Sturgeon Bay were merely two ruts with grass growing between them. Every ten miles or so the boiler would over-heat and blow the safety valve. Mr. Guenzel would have to climb under the car and insert a new one.

Father stayed behind in the Blackstone Avenue house with a fellow member of his department, Clarence Parmenter, both of them having opted to teach for the summer quarter. Father could become so intent on what he was talking about that he could be absent-minded. Parmenter wrote Mother a letter describing Father pouring maple syrup on his head while he scratched the breakfast pancakes.

The year 1912 we spent in Europe, where Father was doing research on the Grail Romances. When we came back to Chicago, we moved to 1220 56 th Street, between Kimbark and Woodlawn.

In 1914 Father again took us all to Europe.

We were mountain climbing in Austria when the Arch-Duke was murdered in Sarayevo. Father became worried when Austria mobilized against Russia and decided to take us to a safe country,—Germany. We arrived in Munich on the morning Germany declared war on Russia and World War I began. We finally got back to the United States by a Holland-American liner during the battle of the Marne.

It was not until 1915 that I became a regular student at the Elementary School. My life there did not start off easily. My mother was ahead of her generation in many things. She smoked, loved to dance, entertained with gusto, had an enormous circle of friends, but she was also a romantic. She insisted on dressing me in short pants and jacket and a shirt with a Buster Brown collar and a flowing black tie tied in a bow.

At school, at ten o'clock every morning, we had a break for roughhousing and letting off steam. Every day one of my classmates, Percy Boynton, would say insulting things about my get-up. I felt obliged to hit him, whereupon he would beat me up. This went on for a time until I found a way to solve the problem: one night I took all my collars, tore them into pieces, -and threw them out my bedroom window into the alley. The next day I went down to breakfast without a collar. My mother asked me, "why no collar?" When I explained, her only comment was, "I had no idea you felt so strongly about them."

But my problem was not restricted to my classmates. In order to get to the Elementary School, I had to pass Ray School , the public school between 56th and 5 7 t One afternoon, walking home from school, I stopped to watch some Ray School boys playing marbles. One of them stood up and asked me what I was looking at. When my answer was not to his satisfaction, he pushed me back over one of his friends who was kneeling behind me. Then they beat me up.

I found out that my tormentors were members of the Musik brothers gang. They were the sons of a tailor down on 55 th and considered themselves bosses of the entire area bounded by Woodlawn and

Kimbark, 55 t and 56 th Streets. The neighboring block on the other side of Kimbark was dominated by the Scotti brothers gang. The eldest Scotti offered to defend me against the Musiks. I became an enthusiastic member of his gang. He was thin, almost emaciated, slightly red-haired; he was my first experience of charismatic leadership. He had a technique of binding the loyalty of members of his gang by getting them to become his partners in some outrageous act. One day he suggested that the workmen who were building some houses on the other side of 56th Street usually left their toolbox on the site overnight. He told me we could use those tools. That night, without a second thought, I lifted the tools and handed them over to him.

There was a third gang on the block between 57 th and 58 th run by the Colissimo brothers. On weekends we would sometimes have football games between the gangs on the Midway. One team or other would grossly cheat and the game would break up into a freefor-all fight. Years later, after I had gone east to school and college, but had come back to Chicago for a vacation, I asked about the Musiks, the Scotties and the Colissimos. They had been caught up in the more serious gang life of those days in Chicago and had been either killed of jailed. None of them were known to have survived as useful citizens.

The South Side of Chicago contained many different worlds. One was the University world inspired by President Harper, one of the great men of his day. In physics the stars were Michaelson, who lived on 58 th

Street. Professor Milliken lived across the street from us on 56th Glen Milliken was in the class ahead of me, but undertook to lead me into the world of science, its theory, its experiments and practice. West of us lived Professor Dixon, a Nobel Prize winning

mathematician. One block to the East lived James Weber Lynn, one of the stars of the English department. James Breasted, the famous historian of Egypt and the ancient world, lived on Woodlawn. Others that I remember were Thorstein Veblen, the economist, Gordon Laing, the classicist, and Thomas, the sociologist. The University Medical School attracted a distinguished group of doctors, including Dr. Sippy who lived on Woodlawn. The Sippys were the only people we knew who had an autbmobile. In fact, they had two. Everyone else, to get downtown, would walk the eight blocks to the Illinois Central Station and take the train.

There was also a distinguished Jewish business community that lived around 47 th Street or even closer to town. They included the Rosenwalds, the Mandels, the Blocks, the Gidwitzes and the Feuchtwangers. One of the Feuchtwangers ended up as the distinguished moving picture director, Walter Wanger. There were newspaper people, artists and lawyers. Finally there were a number of not so distinguished people, but people who seemed to represent the real world, the Chicago of those days.

That real world was physically represented by the soot from the South Chicago steel mills and the odor of the stockyards which would blow at us whenever the wind

was from the west. The Ray School and Western High with its 4000 students, twenty-five percent of whom were black, seemed to me to be the real world of Chicago in those days. James Farrell's Studs Lonigan presents an accurate picture of that world.

Athletics was, of course, very much a part of our lives. I played soccer, basketball and baseball, with vigor but no brilliance. The school organized a variety of activities to widen our experience. On various weekends we were taken to visit one of the steel mills, then one of the meat packing plants in the stockyards, then the Standard Oil refinery in Whiting, Indiana, then a paint factory and the factory where they assembled the Essex automobile, a brand long since abandoned.

We were members of a Boy Scout group doing our daily good deeds. We sold War Bonds in 1917. We acted out current events. We acted in plays, learned to cook, to set type, to use wood and metal lathes and other machine tools, and to knit. It was an advanced and experimental form of education. I guess it did most of us no harm and for many it opened up larger horizons. There were, however, gaps. I learned no American history and I never learned to spell, but that was undoubtedly my fault, not the school's. I just wasn't interested in spelling. For some, however, the school did not provide the proper discipline.

In my second year at U High, I found myself sitting at an adjoining desk to Dicky Loeb in a French course. Dicky was older and in the class ahead of us. He seemed to me to be charming but soft. During the final examination I noticed that he was cribbing from what I was writing.

Nevertheless I was shocked when it came out that he had joined Leopold in the infamous murder of the Frank boy.

I have left out one important aspect of those years, the impact of World War I upon our emotions and our thoughts. The Nitze family is entirely of German ancestry. Until the war, I had spent about half of my life abroad, much of it in Germany. The people I had known in those pre-war years in Germany, and also in Italy and Austria, were warm, loving, and much more emotional and outgoing than my contemporaries in Chicago, particularly those who were not part of the University enclave. My family was firmly on the side of "Keep America out of the War. In 1917, when the United States entered the war, we switched our views, but doubts remained. My classmates and I were asked to call at houses in our neighborhood and try to sell Liberty bonds. I was utterly surprised when a number of those I called on agreed to buy them. I sold $ 5000 worth of bonds which seemed to me to be an enormous amount.

But even at the age of ten and eleven the unutterable tragedy of the battle of the Somme, of the continuous struggle for Verdun and the mysterious battles on the Eastern front left a lasting impression.

When President Wilson announced his Fourteen Points it seemed that a gleam of hope had appeared in a destructive and irrational world. When the armistice was announced our parents took us to a friend's office high up above Michigan Avenue from which we could watch the parade. But later when the surrender terms and the terms of the Versailles Peace Treaty were announced, I felt bitterly disillusioned. In our current events class we acted out the signing of the Versailles Treaty. I was given the role of Walter Rathenau, who signed for the Germans. Later, Keynes' "The Economic Consequences of the Peace" confirmed my worst suspicions of that treaty.

By 19239 1 had accumulated enough credits to have a chance at being accepted at the University that fall. Father wisely decided that this was a bad idea; I was not only too young, but a University professor's son. He correctly judged that I would not be accepted as an equal so he sent me off to Hotchkiss for two years of growing up. There I didn't learn that much that I hadn't already been exposed to at U-High, but I did have a chance to catch up in maturity—whatever that means—with my peers.

Paul Nitze went on to serve in various roles in the U.S. government—among them: as Vice Chairman of the US Strategic Bombing Survey (1944-46), for the State

Department (1950-53), as Secretary of the Navy (196367), as Assistant Secretary of Defense (1973-76), and was named special advisor to the President on Arms Control in 1984. For over forty years, he was one of the chief architects of U.S. policy toward the Soviet Union.

On January 19, 2001, just one week before his 94th birthday, the USS Nitze was named for him "to sail around the world and to remind us of the contribution you have made to our country"—so said William Cohen, Secretary of Defense.

To the Point:

From the HPHS Newsletter, February, 1982

Muriel Beadle reports on a talk by Ezra Sensibar

It was in 1913 that Marshall Field gave $4 million to erect a natural history museum on the lakefront, on land to be created for that purpose. (Bear in mind that at the time the IC tracks ran on a trestle in the lake all the way from the Promontory to 18th Street, and that there was water 40 ft deep where the Field Museum, now stands.

The initial plan was to fill the site with clay, then cover it with sand. That combination, however, turned out in actuality to be mush", and it was decided to combine clay and rubbish (collected from

Loop offices, stores and streets) and top that with sand.

Once the fill was complete, wooden piles were driven down through it to the former lake bottom, and concrete piers were superimposed on the piles. These piers, which support the basement floor of the museum, rise to a height of 42 feet above the level of the lake and in effect place the museum on a manmade hill.

Tracks were laid to give railroad dump cars access to the site, and sand was hauled in. When dumped, though, its weight and force pushed some of the piers out of line and made them unusable as foundations.

What to do? "The marble was piling up," Mr.

Sensibar said. "The architects were tearing their hair.

Nobody seemed to know how to solve the problem."

And then a 24 year old Gary, Indiana resident, Jacob Sensibar (Ezra's older brother) had a bright idea. He was no engineer—in fact he was fresh off the farm— but he had eyes and a brain. "Why not lay down the sand the same way a beach is built up—that is mixed with water and deposited gently on the site?" he asked.

The architects decided to try it. Marshall Field loaned young Sensibar $40,000; Jacob bought a boat and equipment and began to pump in sand and water; and his system worked. So it is especially appropriate that the firm he founded has been identified with so many of Chicago's subsequent lakefront construction projects—including Promontory Point.

A Page from Cap and Gown the University of Chicago Yearbook—1903

The Woman's Union

Among all the student organizations at the University none as ever been so far reaching in its benefits, so practical in its advantages and so democratic in spirit as the Woman's Union, organized in January, 1902, "to unite the women of the University for the promotion of their common interests." Starting with a mere handful of faithful and enthusiastic workers, including both students and women of the Faculty, the membership has grown to almost four hundred... But the success of the Union is not measured by the length of its registration alone, for the benefits derived from membership are varied and along several lines.

Formerly all women connected with the University who did not live at the halls or near the Campus brought their lunches with them, and the only accommodations for eating them, or for resting were in the cloak rooms and recitation rooms. Now all that is changed. In the Union rooms, which are at Lexington Hall, the new woman's building, lunch is served every day from 12:00 to 2:00 p.m., and for a moderate sum, soup, chocolate, sandwiches, fruit cake and pickles may be obtained.

Other special accommodations are a rest room and reading room, in which may be found the daily paper and all the late magazines. Here, every day, from fifty to a hundred girls meet to eat, and chat, and rest. It is one of the unwritten laws of the Union that no stranger be allowed to eat luncheon alone, so that the Union, while offering material advantages, is also doing a great work along another much needed line. It is fostering and developing a spirit of equality and democracy which gives promise of a bright future... The girls enjoy not only the advantage of becoming acquainted with each other, but also the privilege of meeting wives of the faculty and other women.

Along business lines the Union has not only been self-supporting, but has to its credit in the bank a sum amounting to $67.73.

PLEASE JOI N US FOR

THE HYDE PARK HISTORICAL SOCIETY

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 2002 THE QUADRANGLE CLUB

SPEAKER Peter Ascoli

TOPIC My Grandfather, Julius Rosenwald

GATHERING 6PM • DINNER 7PM

ELECTION OF OFFICERS

CORNELL AWARDS

MAR K YOUR CALENDAR FOR

SUNDAY, MARCH 3, 2002

2-4PM

AT OUR HEADQUARTERS

Claude Weil

former resident and staff member

WI LL SPEAK O N

International House,

Its History and Vision

1932 to the Present

AND ENJOY OUR EXHIBIT ON INTERNATIONAL

HOUSE COMPILED BY STEVE TREFFMAN,

BERT BENADE, CLAUDE WEIL, DENISE JORGENS, MARTA NICHOLAS

AND PATRICIA JOBE

SPECIAL MESSAGE

Mary Ellen Ziegler and I are creating a website on the

Outdoor Public Art (Sculpture and Murals) on the South Side. We would welcome anyone with knowledge of the subject to contact us at (773) 288-1242 or at jamulberry@aol.com. Thank you! —Jay Mulberry

LOOKING BACK

Some excerpts from PROGRESS, (Newsletterfor A Century of Progress) March 29, 1933

Bridge To Be Important Feature

Of Entertainment At Exposition

Wing of Hall of Science Designated as Bridge Hall;

United States Bridge Association To Direct Activities

Bridge, the pastime of millions, is to be an important feature of entertainment at A Century of Progress. An entire wing of the Hall of Science at the Fair has been designated as Bridge Hall, and the

United States Bridge Association has been selected by A Century of Progress as the organization to plan and operate the various Bridge activities at Bridge Hall.

George Reith, Executive Vice president of the Association, announces that there will be an interesting historical exhibit in the tournament hall showing the evolution of bridge and he expects several museum exhibits in this feature.

In addition to daily afternoon and evening play for suitable trophies, there will be featured weekly best score play for valuable prizes such as automobiles, bridge furniture, etc. It is also expected that many sectional tournaments, the winners of which will qualify for the national championships, will be held at the Fair...