Hyde Park Stories: Cheney-Goode Memorial Bench

Written by Patricia L. Morse

The bench tucked under the railroad embankment at the east end of the Midway Plaisance is easy to miss. The grey paint is chipped and faded, the inscription weathered. It’s just possible to trace the words: “Leaders who devoted their lives to the civic betterment of their neighborhood, city, and state; Katherine Hancock Goode 1872-1928; Flora Sylvester Cheney 1872-1929.” Who were Goode and Cheney, and why do they have a bench?

They were a team for women’s rights and civic improvement. Cheney was the shrewd campaign manager, Goode the charismatic public speaker. They were once nationally renowned. They were two of the four Illinois women placed on the National League of Women Voters honor roll, joining women like Jane Addams and Susan B. Anthony. Illinois was a hotbed of suffrage, and Hyde Park/Woodlawn was ground zero. When the Republican Convention came to Chicago in 1920, 40 women from the neighborhood descended on the convention on horseback through a driving rain to demand the vote.

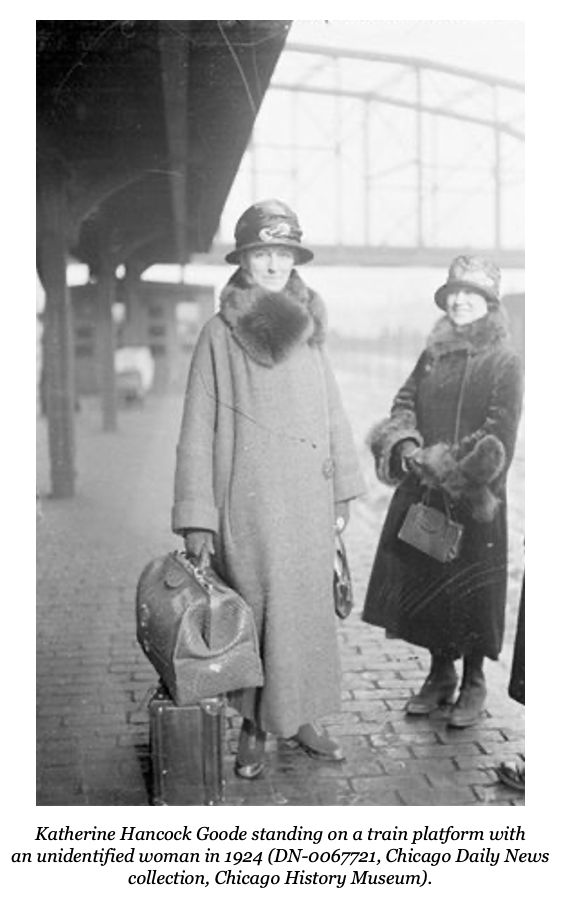

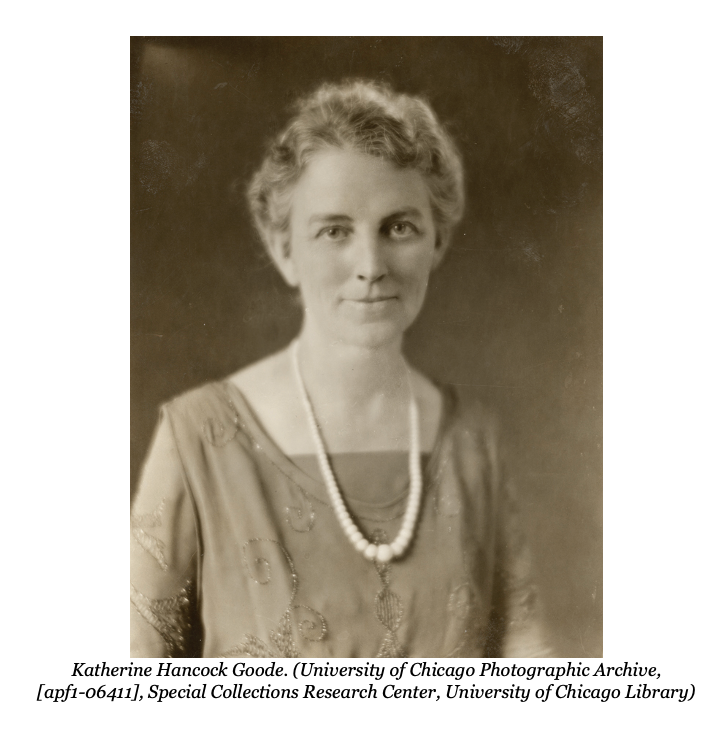

Katherine Hancock Goode was born in Minnesota, became a teacher at 14, and found a teaching job in Philadelphia, where she met and married J. Paul Goode, a renowned cartographer. They moved to Chicago (6227 S. Kimbark) in 1903 when her husband joined the Geography Department of the University of Chicago. They spent a sabbatical in China. She was a leader of the Woodlawn Woman’s Club and a force in the Political Equality League, the activist wing of the Chicago Woman’s Club. It organized marches and petitions, taught classes on political, legal and economic issues, debated women’s roles, supported striking women workers, and promoted the welfare of children. Women had been fighting for the vote in Illinois since 1855. In 1891, women gained the right to vote for school boards. The women’s clubs organized in every Illinois senatorial district and managed to get the right to vote in state elections in 1913. When the 19th amendment passed Congress in 1920, Illinois was the first state to ratify, beating Michigan by an hour. Women then reorganized as the League of Women Voters, a nonpartisan force for good government. The first state to form a League chapter was Illinois, and the largest local chapter in Illinois and perhaps the country was Hyde Park/Woodlawn.

Goode traveled the Midwest with a speech called “Let Women Mind Their Own Business” to persuade hesitant women to join the fight for better education, housing, and sanitation. These, she argued, had always been women’s concerns. She was effective, as the Rock Island Argus reported: “Mrs. Goode in her charming, simple, motherly way, held her audience so completely that although the hour was unusually late, not a move was made except in giving the applause.” In December 21, 1926, Katherine Goode gave the Convocation Address to the University of Chicago on “Woman’s Stake in Government.” She realized that creating change meant legislation. Cheney became her campaign manager, and Goode became one of the first four women in the legislature.

The Tribune gave an account of what that was like: “amid sweat and tobacco smoke and slithering and bluff and bellow and browbeating and fawning and bombast and some booze, hundreds of millions are being legislated away…. Amid the heart-sickening hullabaloo, …. a woman rises from her desk—Representative Katherine Hancock Goode….The hour is late, the heat cruel, and Mrs. Goode must be weary, but she meets an emergency gallantly. The member who was to have spoken on the bill [to move Cook County jail]…is found to be—and here I speak literally—'in no condition to speak.’ Mrs. Goode must speak for him. She does, and she speaks well….She knows what she is talking about and so is brief. Her words are well chosen, she is applauded.” She fought for the eight-hour day, women on juries, and better conditions for incarcerated women.

Goode ran unopposed for re-election, but in the next session, influenza came to Springfield. Eight legislators, including Goode, died within months. Cheney stepped in to complete her friend’s term.

Flora Sylvester was a teacher in Wisconsin when she married Henry Cheney, who was a graduate of the University of Chicago Medical School. They soon moved to Chicago (6041 S. Kenwood) where Henry became a prominent physician. Flora Cheney had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which had no treatment at the time, but that didn’t stop her. Her political base was Woodlawn, starting with the Woodlawn Woman’s Club. She was the executive chairwoman of the Woodlawn Community Center for 13 years. She was an organizer of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association. With the vote in 1920, Cheney became the first president of the Illinois League of Women Voters, editing and writing the newspaper.

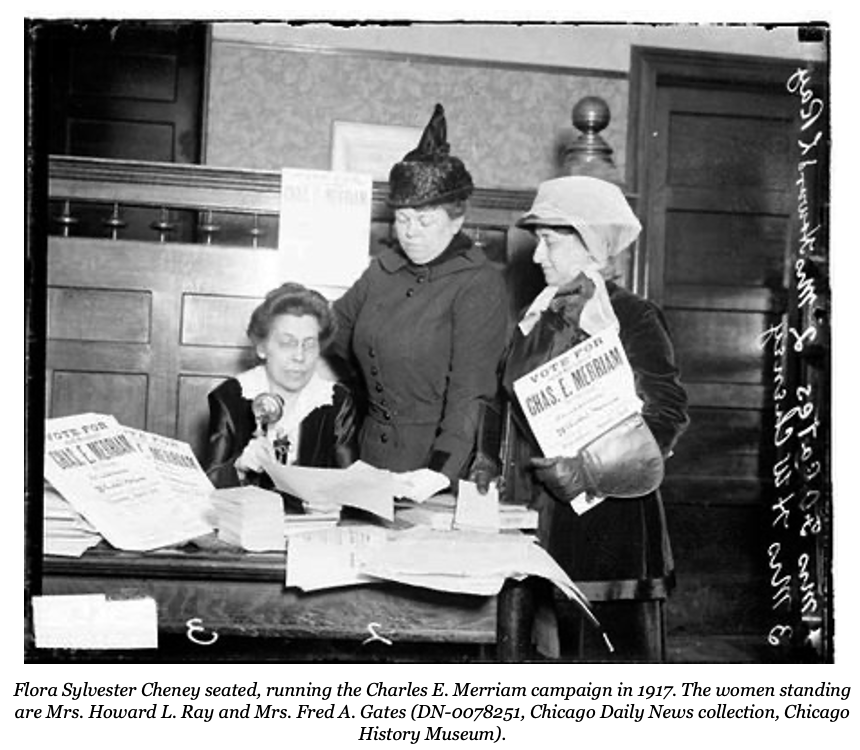

In her articles, Cheney made clear that the vote wasn’t the end of organizing; voting was the means to create change. When the Tribune called the League “doomed” because no one wanted nonpartisan reform, Cheney insisted, “We shall succeed.” Later, Cheney ran several political campaigns, including reform candidates Dever for mayor (against corrupt Big Bill Thompson) and Charles E. Merriam for alderman. Cheney’s daughter married Charles E. Merriam’s son. The Herald called Cheney “a shrewd and powerful campaigner,” skillfully deploying slender financial means.

Cheney’s re-election campaign was supported by progressives like Lorado Taft and Jane Addams. Her opponent, Mrs. William Fetzer, while claiming to be a friend of Katherine Goode, was the candidate of Big Bill Thompson’s machine. Cheney handily defeated her but, exhausted, succumbed to Hodgkin’s. Flora Cheney’s memorial service filled Rockefeller Chapel. The legislature honored her by passing a bill she’d proposed, the very outcome Thompson tried to prevent. The Cheney Act established a commission to reform elections by tossing out 100 contradictory pages of laws that suppressed the vote.

A committee looked for a suitable memorial. The relatively new square on the east end of the Midway was central to their legislative district--empty and visible. A gleaming limestone bench and sundial there would remind passersby of the women who gave, as the Herald said, “to the limit of their endurance.” The committee pictured it as the focal point of a memorial garden dedicated to Goode’s and Cheney’s “righteous indignation against special privilege and the exploitation of the helpless.” For decades, the bench was the only monument to actual women in a Chicago park. It’s still one of the very few. The Park District never planted a garden, the sundial was soon stolen, and the bench disappeared under the dark paint used to cover graffiti. The plans for the east end of the Midway include the restoration of the bench. I hope Goode and Cheney finally get the recognition they deserve.

A shorter version of this article appeared in the Hyde Park Herald, October 18, 2021. Hyde Park Stories: The Cheney-Goode Memorial Bench | Evening Digest | hpherald.com